A rapper who has more records released posthumously than they did during their lifetime is usually a warning sign. Diminishing returns. Bleeding the well dry. Scraping the barrel. These phrases certainly spring to mind when listening to “Harlem’s Finest”, a modern re-imagining of freestyles and re-purposed verses from previous tracks, masquerading as a new Big L album. Maybe I’m viewing this through the lens of someone who thinks the Mobb Deep and De La Soul albums were excellent – unexpectedly so – therefore, this Big L album was always going to be a disappointment. It’s a different proposition, one that was never really going to add much to L’s legacy. To understand why “Harlem’s Finest” is difficult to rate as a Big L fan is to know what has come before.

1995’s “Lifestylez Ov Da Poor N Dangerous” is widely considered a classic in hip-hop circles – this website included – and 2000’s “The Big Picture” has gradually grown in reputation over the years as a fine celebration of L at his best. It elevated him from the grimy sound of “Lifestylez” to a more polished artist, showcasing his writing ability and collaborating with legendary names like Big Daddy Kane and Kool G Rap. Both albums are essential texts for any fan of lyricism, and they showcase why Big L is viewed so favorably, particularly amongst the quick-witted punchline rhymers that emerged in the 90s. Big L was sadly gunned down in the lead-up to “The Big Picture” coming out, and he didn’t live in the studio like Tupac Shakur did – the vaults weren’t blessed with albums’ worth of songs. Fortunately, Big L’s style and strength lay in his playful freestyles – one of his most famous was included on “The Big Picture”. Rawkus Records, which released “The Big Picture”, quickly followed it up a year later with the promotional compilation “Harlem’s Finest: A Freestyle History”, but this is not only rare, it’s blocked from sale on Discogs. Similarly, there were two unofficial releases on Corleone Recordings: “Harlem’s Finest: A Freestyle History Vol. 1 & 2” dropped in 2003, and “The Archives 1996-2000” was released in 2006 but limited to 500 copies. It was pretty common to see unofficial CDs in stores, no doubt trying to cash in on a beloved rapper, but these were generally non-canon, and most rap fans may have missed these (I know I did). 2003 saw the release of “Live From Amsterdam” – recorded footage of Big L and his D.I.T.C. comrade A.G. performing at the 2-year anniversary of Fat Beats Amsterdam in 1998. There was also the shifty “Rare Tracks EP”, which had 300 copies pressed in Switzerland, which gives you an idea of how Big L was a favourite in Europe, and not just a New York phenomenon. His catalog was getting pirated all over the globe.

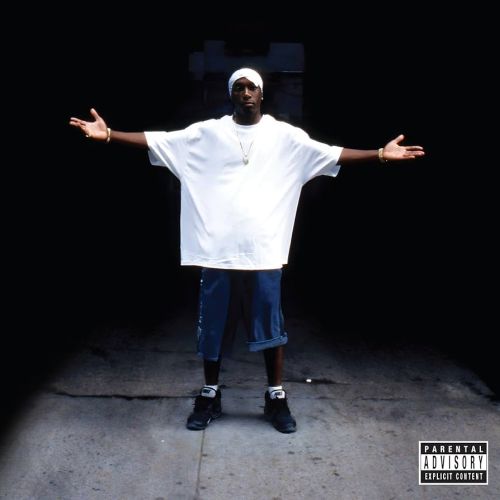

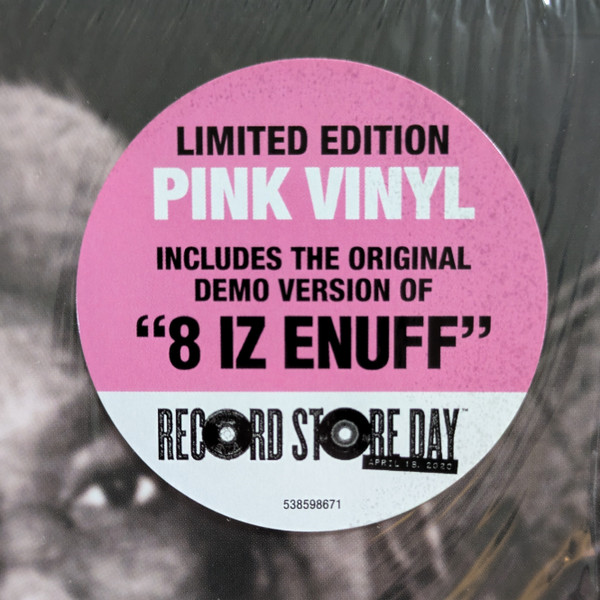

The Big L estate had managed to put out something official by 2010, with “139 & Lenox” on Flamboyant Entertainment compiling some of these unofficial freestyle tracks, along with remixes of singles like “Ebonics” and “Platinum Plus”. It was solid stuff. I remember purchasing the next Big L release: 2011’s “Return of the Devil’s Son”, which genuinely felt like it had some new songs on it. Looking back, many of these tracks were renamed and repurposed from mixtape appearances, but “Sandman 118” and “Devil’s Son” at least played into the darker concept behind L’s evil persona he frequently teased. At 21 tracks, it was also comprehensive in its coverage of unreleased and recovered verses. Therefore, I was surprised to see another compilation by Big L released in 2020, called “The Danger Zone”. This one was definitely a cash-grab, as it coincided with Record Store Day, had poor audio quality, and was available in pink vinyl. I cannot envision Big L, infamous homophobe (stating on the track “Danger Zone” that he’s “fast to put a cap in a fag chest“) endorsing this:

This takes us to 2025, where Big L has been resurrected once again for another selection of freestyles to be paired with different beats and a higher-profile collection of guests. For the Big L fans, here’s a quick reference guide to relieve those frowns and sense of deja vu:

| 2025 track | Where you’ve probably heard it before |

| Harlem Universal | Universal Freestyle (2010), NY Freestyle (1999) |

| U Ain’t Gotta Chance | Tim Westwood Show Freestyle (1997) |

| RHN (Real Harlem N****s) | Sandman 118 (1995, 2011) |

| Fred Samuel Playground | Double Up (2010) |

| All Alone | Alone (1997) |

| Forever | Keep It Ghetto Freestyle (2003) |

| 7 Minute Freestyle | With the Milkbone Keep It Real beat |

| Doo Wop Freestyle ’99 | This is actually the second part of the freestyle; the first part is included on The Big Picture (2000) with the famous “Ask Beavis, I get nothin’ Butthead” line. |

| Stretch & Bob Freestyle ’98 | This is actually the second part of the freestyle; the first part is included on The Big Picture (2000) with the famous “Ask Beavis, I get nothin’ Butthead” line. |

| Grants Tomb ’97 | This is the other part of Keep It Ghetto Freestyle (2003) |

| Live @ Rock N Will ’92 | Rock N Wills Audition (2003), Audition (2011) |

| How Will I Make It | How Will I Make It (2003), I Won’t (2011) |

| Put the Mic Down | Back Up Off Me (1998) |

What’s interesting about all of these Big L releases is that they never feature his Diggin’ in the Crates crew. Lord Finesse, Fat Joe, OC, Buckwild, Diamond D? Nowhere to be found. I’ll give Mass Appeal credit here, though, because the guests seem to have been carefully chosen. Lead single “U Ain’t Gotta Chance” is one of the best reasons to pick this album up. After Big L burst onto the scene with his track “Devil’s Son” in 1993, using a snippet of Nas from his first appearance on “Live At the BBQ” (1991), it feels like a natural collaboration. Some real devious tactics are occurring here, too, as Nas not only adopts a Big L flow; he fires some stray shots at Jim Jones (who grew up in Harlem):

“A firearm, fire Timbs, but this year’s the year of the disrespectful comparisons

They jack anything on the internet, stupid kinda

Believe in that, you believe in chupacabra

Making funny music, it’s doo-doo, caca“

Speaking of Nas, I wouldn’t be surprised if he insisted that “7 Minute Freestyle” was digitally remastered and made the centrepiece of the album. Big L is trading verses with Jay-Z, but it’s bordering on bullying with how a younger L steals the shine from Jay. Method Man is along for the ride on “Fred Samuel Playground”, a grimy Conductor Williams track that reveals how L used to sell Meth PCP (taken from a Drinks Champs interview). Considering how many Big L verses are here, this Method Man one is the best performance on the album – his albums haven’t been much cop, but Meth’s verses in the last five years have been superb reminders of the Wu-Tang Clan star’s ability. If anything, he’s improving every year. Joey Bada$$ is another canny inclusion, this time on “Grants Tomb ’97”. He was always going to fit this type of production, and he doesn’t threaten to outshine nor overindulge in Big L, simply complementing the song:

In the 2000s, many rap purists would vouch for Big L as one of the greatest rappers of all time. It’s something his friend McGruff does on the first track, “Harlem Universal”, but I was very much one of those teenagers who proudly proclaimed Big L was one of the best. The inclusion of Mac Miller on “Forever” is an interesting one, because his fanbase similarly build their personality around this elevated take that L (or Mac) is one of the greatest of all time. Neither of them are, let’s be blunt, but both are special emcees, and it’s not hard to see how Mac was influenced by Big L, something he admits:

“That’s what it is, but as far as bein’ an emcee, you know

The first rapper that really got me into wanting to be an emcee was a dude by the name of Big L“

Up-and-coming emcee Errol Holden gets the spotlight on “Big Lee & Reg”, an odd decision that nonetheless does capture some of the vibes of Big L. Almost as if this would be how he sounds if he were born twenty years later.

It’s good that this is an official release with some remastered vocals, but unless you’re new to Big L, it’s difficult to know who this record is aimed at. Big L fans have heard this all before, and if you’re looking to listen to Big L, his earlier material is superior in every way. That said, it’s still Big fuckin’ L, so the bars and beats are generally on point. What’s evident, perhaps more now than ever, is that Big L was very much a 90s rapper, which means you’re going to get some misogyny, some homophobic slurs, and some dated references. Mass Appeal even had to censor “I’m keen to bust a mean nut in some teen slut” on “Fred Samuel Playground” because, well, I don’t need to explain why. Big L had a dark sense of humor, but also flirted with horrorcore, and some lines just don’t hold up even if he was referring to an 18-year-old.

I also think that the more you listen to Big L, the more his formula unravels into a repetitive structure behind his verses. Granted, his formula is potent; Lord Finesse with extra charisma, but songs like “All Alone” remind me how powerful L’s pen could be when given a theme or topic to explore beyond the bravado and posturing. It’s why “Ebonics” remains iconic. That may be the greatest loss from Big L’s passing 25 years ago – he was just getting started. The freestyles were fun, but he was just flexing his muscles. “Harlem’s Finest” certainly focuses on those humorous one-liners and internal rhyme schemes that his reputation was built upon, but it also confirms why people do include him in their Top 5 emcee lists. The potential was limitless. Nas was rightfully scared of sharing a mic with him, and made sure he was buried for quarter of a century before engaging the idea. Big L was a menace to emcees, and while the hardcore fan in me pores over every recycled rhyme with hesitation, there’s no denying that an official collection of his verses, restored and presented to a new generation, is an important reminder for any rap fan, no matter how many times we’ve heard them.