For a time in the late eighties and early nineties, many people involved in hip-hop thought that the number one threat to the culture was hip-hop going pop. Hip-Hop was first and foremost from the streets and for the streets, and the idea of a rapper trying appeal to (white) mainstream pop culture was deeply offensive to many people in hip-hop. The fear was that this vibrant culture, which represented the voice of young black America, would be co-opted, defanged, and watered down by the mainstream. White people were going to steal and mess up hip-hop just like they did jazz and rock n’ roll.

As a result, rappers that had crossover success into the pop mainstream were scrutinized, ridiculed, and cast out of hip-hop by its gatekeepers. There was no regaining cred once you went pop. That’s part of the reason why Vanilla Ice is doing reality shows and robbing houses, and why MC Hammer hasn’t had a top 10 hit since parachute pants went out of style. A Tribe Called Quest, 3rd Bass, N.W.A, Ice Cube, and even the Beastie Boys called out rappers’ attempts to go pop in song. The best way to lose your cred as a rapper circa 1990 was to appear to be courting the mainstream.

People took this seriously. Serious enough to fight over it, and not just on record. Ask Prince Be of psychedelic hip-hop group P.M. Dawn, who was punched by no less than the Teacher himself, KRS-One. In an infamous event, KRS-One and his crew stormed the stage while P.M. Dawn were performing at the Sound Factory in New York in 1992, punched Prince Be and threw him off the stage. KRS-One was allegedly reacting to feeling disrespected by Prince Be in an interview, but to many hip-hop fans, it seemed like he was defending real hip-hop against interlopers. But did hip-hop need protection against P.M. Dawn? Were they a lame attempt at pop crossover, or a group trying to do their own thing that got unfairly targeted? At the time, I thought that KRS-One was being a bit of a bully coming after Be. Let’s revisit P.M. Dawn’s debut and see if history is on their side.

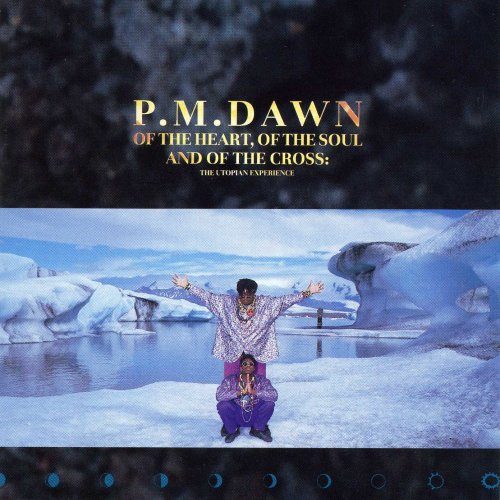

P.M. Dawn started in the late 80s by brothers Attrell and Jarrett Cordes, aka Prince Be and DJ Minutemix. They were signed to now-defunct British label Gee Street, home to other leftfield hip-hop acts like Stereo MCs, Jungle Brothers, and Gravediggaz. In some ways you can credit (or blame) De La Soul for P.M. Dawn’s success. “Of The Heart, of the Soul, and of the Cross: The Utopian Experience,” came out two years after De La Soul’s “3 Feet High and Rising.” It feels inspired by “3 Feet High,” not only in De La Soul’s hippie vibe, but their use of nontraditional samples. De La Soul proved that rappers could work outside the confines of soul and funk. They sampled Steely Dan, Hall and Oates, and Johnny Cash, and turned those samples into solid rap songs.

P.M. Dawn took this one step further by sampling New Wavers Spandau Ballet’s ultra-white, ultra-wimpy ballad “True.” They flipped that sample into gold on “Set Adrift on Memory Bliss,” combining it with the drums from Eric B. and Rakim’s “Paid In Full” to keep things hip-hop. The song was a #1 hit, helped “The Utopian Experience” sell over 500,000 copies. As you can probably tell from its title, “Set Adrift on Memory Bliss” was not your typical rap song. It took a psychedelic approach to hip-hop, turning what could have been a standard love rap into something weirder:

“A careless whisper from a careless man

A neutron dance for a neutron fan

Marionette strings are dangerous things

I thought of all the trouble they bring

An eye for an eye, a spy for a spy

Rubber bands expand in a frustrating sigh

Tell me that she’s not dreaming

She’s got an ace in the hole, it doesn’t have meaning”

There’s another major influence on P.M. Dawn, beyond De La Soul and the Beatles’ during their Magic Mystery Tour period: the hip-house sound of Soul II Soul. P.M. Dawn used similar drums on their songs, and also combined R&B and dance music with hip-hop. A song like “Paper Doll” has as much in common with “Back to Life” as it does with anything De La was putting out. In fact, when I was looking for this album to review, I found it shelved in the R&B section of Amoeba Records rather than the hip-hop section. It is just as much an R&B album as it is a rap album.

One of the selling points of P.M. Dawn when they came out was their new age hippie schtick; it certainly set them apart from any other rap group out in 1990. Just look at the video for “Set Adrift on Memory Bliss.” They are fully decked out in African-print t-shirts, headbands, John Lennon glasses, and have bracelets for days. They took the Afrocentrism of the Native Tongues crew and gave it a sixties twist. Even today, their sound and lyrics set them apart from most other hip-hop.

While “The Utopian Experience” has psychedelic elements, P.M. Dawn weren’t eating mushrooms and dropping acid as much as they were new age mystics. As a result, “The Utopian Experience” feels more new agey than trippy, and the lyrics are sometimes a little goofy. The album certainly isn’t as drug damaged as Redman’s “Dare Iz a Darkside,” or as trippy as Edan’s “Beauty and the Beat” or Quasimoto’s “The Further Adventures of Lord Quas.” On “Even After I Die,” Be is talking to God, with lines that are alternately deep and silly:

“The thought of You just reeks with divinity

A spark by my heart is the symbol of the Trinity

I can understand that the stakes are high

But I’d really like to know what I’ve done and why

I’m floating in a sea of doubt when it comes to that

It seems as though all of my thoughts are now acrobats

I am you, now that’s a thought to renege

But in the thought that stops it seems to get big

I wonder why Father, why it is? What it is?

Because I am what I am, what gives?”

One of the legacies of “The Utopian Experience” is how it predicted hip-hop’s shift towards embracing R&B, embracing pretty production, and embracing psychedelics. Listening to the album today, it’s hard to imagine a rapper getting mad at how pop it is. Nowadays, even the toughest rappers sing their hooks and rap over pretty beats, A$AP Rocky is rapping about dropping acid, and there are multiple sub-genres of alternative hip-hop.

That wasn’t true in 1991, when I first bought this album. I was looking for hip-hop that was less nihilistic than the West Coast gangsta rap that was all around me. At the time, I was excited by the idea of someone taking hip-hop in a different direction and making music that was more concerned with spiritual questions rather than macho posturing. As much as I wanted to love “The Utopian Experience” as a sixteen-year-old hip-hop fan, I had a hard time getting into it. Listening to it twenty-four years later, it holds up better than I remembered, although some of the problems I had with it at 16 still hold true.

For one thing, the lyrics aren’t always great. As I mentioned before, there is some goofiness to Be’s attempts at being deep and metaphysical. His drippy “What is reality, man?” gets old, and his mystic pacifist vibe doesn’t make him the most engaging rapper. Also, their attempts to mash up hip-hop, house, and R&B don’t always work. “Set Adrift on Memory Bliss” and “Paper Doll” both sound really cheesy to my ears now, and their dance song “Shake” downright bad. It is also dated in the way that all old hip-hop is dated: Be has a 90s flow and Megamixx is using 90s tech to make 90s beats, all while wearing some serious 90s fashion and rapping about 90s things. The datedness works in its favor at times: “To Serenade A Rainbow” and “Reality Used to Be A Friend of Mine” reminded me of early De La Soul and “Comatose” sounds like an Ice Cube beat. If you are a fan of early 90s hip-hop production, there are some gems on “The Utopian Experience.”

Beyond the 90s production, what makes “The Utopian Experience” worth re-visiting (if you can find a copy – it’s out of print, possibly because of sampling issues) is the way in which Be and Megamixx pushed hip-hop out of its comfort zone. It was gutsy for Be and Megamixx to be as wimpy as they were on this album. It took courage to make a song that sampled a new wave ballad, or was built around a Beatles sample. They made music with none of the posturing, either lyrical or musical, that was the basis of most hip-hop in 1990. Be’s lyrics aren’t about bragging, cutting down sucker MCs, or partying. They are about talking to God, questioning the nature of reality, and talking about love in metaphysical terms.

True – they were following on the heels of De La Soul, who had started the whole hippie rap thing (and just as quickly vehemently disowned it), but P.M. Dawn took it further than any other group. Even in 2015, most hip-hop is confined to themes of urban America. Very few artists use rap music to explore other realms of thought and realities the way P.M. Dawn attempted to. If anything, rap post-1990 became even more obsessed with “keeping it real,” even when that meant fantasies of violence and wealth that bore as little resemblance to day-to-day life as what Be was rapping about.

Be’s altercation with KRS-One happened in 1992, a year after De La Soul disowned the D.A.I.S.Y. Age on “De La Soul Is Dead,” and a few months before Dr. Dre’s “Chronic” came out and changed the sound, subject matter, and coastal epicenter of hip-hop. P.M. Dawn’s 1993 follow-up “The Bliss Album…?” went gold, so neither “The Chronic” nor KRS-One’s public rebuking of them seemed to have hurt the duo’s prospects. The two albums they released after that failed to chart, and since then Be has had multiple strokes and amputations; his cousin Dr. G tours under the P.M. Dawn brand, but without either founding member. A quarter century later, “The Utopian Experience” doesn’t feel like a lame crossover grab, but rather an attempt to go somewhere totally different with hip-hop. It’s unfortunate that so few artists followed the trail that P.M. Dawn made; hip-hop could use more weirdos and outcasts.