When the news of Mac Dre’s death started to spread in early November 2004, a lot of people might have wondered just who this Mac Dre was. Coincidentally, RapReviews.com, after ignoring the rapper’s relentless output for years, had finally given him his due shine just shortly before. First Steve ‘Flash’ Juon covered “The Genie of the Lamp,” followed by new recruit Pedro ‘DJ Complejo’ Hernandez, who on October 19th had a look at “Tha Best of Mac Dre” and took the opportunity to take us back to 1993’s sort of best of “Young Black Brotha – The Album”. Inspired by my colleagues, I began working on something myself, which now sadly is our first posthumous Mac Dre review. The bias couldn’t be heavier than when an admitted fan writes about a deceased idol, but would you let a complete stranger deliver a eulogy? Probably not. Therefore, I view it as my duty as Mac Dre fan and contributor to this website to at least cover one Mac Dre album.

Should you have been familiar with Mac Dre? With so many Mac’s and Dre’s in the game, what can a Mac Dre have to offer that you haven’t heard already? For the average couch potato it’s hard to notice a rapper who is without crossover hit and major label backing. But not all the good stuff can be found in the crevices of your couch. Sometimes you have to get off your ass if you want something. And you shouldn’t depend solely on TV to tell you to get off said ass. Still, there has to be some kind of initial exposure. A cousin on the other side of the continent who comes for a visit and brings some tapes along. An uncle who introduces you to old school rap. Even if you’re like me and simply let your own curiosity guide you through the record store, the record has to be available. Still and all, the possibility is there that you manage to make yourself familiar with something or someone you didn’t know existed. Luckily, I was granted that opportunity to become a fan of Bay Area mob music and consequently Mac Dre. But I too was a neophyte, a new jack, probably first hearing about Mac Dre roughly ten years ago. By then, he was already a veteran to the game, having made his debut in 1989. While his untimely death made him join the ranks of hip-hop’s immortals, Mac Dre had long before become a Bay Area rap legend, whose professional career would have spanned well beyond the 15 years we’re now looking back at.

A prison term is often the stuff rap legends are made of, and the case of Mac Dre being convicted of conspiring to rob a bank in Fresno was certainly a highly infamous one that lead many to believe the rapper simply served the authorities as a scapegoat. Without much more information at hand than what The Source and Bay Area journalist Davey D reported, it’s actually quite feasible that he was just sympathizing with a local crew of hoodlums who were able to fool the police. The rapper told his side of the story in 1992, first while he was still free (“Punk Police”) and later when he had been arrested (“Back n da Hood”), his feelings summed up by the words:

“Punk police with a one-track mind

Man, you can’t even find who’s been robbin’ you blind

It got deep, so you had to blame somebody

What’s next – you gon’ frame somebody?”

But in the end it takes more than war stories and court cases to become a rap legend. Charisma and originality are key to getting people to listen to you rather than someone else. Otherwise, you’re just another Mac, or another Dre. But Andre Hicks was not just another rapper. He drew you in with his easygoing, conversational tone, with his humor and his wit. With his game, as people out west would say. It would be easy to dismiss someone as shallow who flat out calls one of his albums “It’s Now What You Say… It’s How You Say It.” But one only needs to listen to Dre’s more prolific work to realize that, like another album title of his suggested, the man possessed the “Heart of a Gangster, Mind of a Hustler, Tongue of a Pimp.”

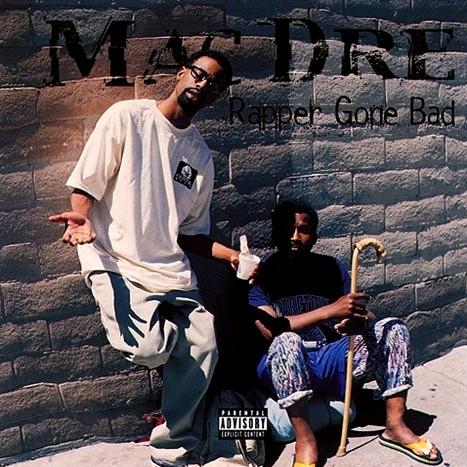

That doesn’t mean that he actually WAS a gangster, hustler or a pimp, but that his music drew from the qualities these characters embody. So Mac Dre wasn’t the most complete rapper, but then again who is? Many are not even good at what is supposed to be their forte. Mac Dre stuck to what he knew best and excelled at it. The shortest possible portrait is his own self-description from “Rapper Gone Bad” – “a thug like 2Pac,” “mack like Too $hort.” But the operative words here are thug and mack, not the two high-profile names. In the Bay, Mac Dre was a star himself, and while he was certainly influenced by Todd Shaw, his own influence on Tupac Shakur cannot be lost on anybody who listens to early Dre cuts like “Young Black Brother,” “Too Hard for the Fuckin’ Radio” and “California Livin’.” With the name-dropping underway, it should be noted that Mac Dre and his substitute Mac Mall both in name and in nature paid tribute to the patron of this Vallejo rap dynasty, Michael ‘The Mac’ Robinson, who was himself murdered in 1991. The name of Mac Dre’s last studio album, “The Game Is Thick Part 2,” was a reference to The Mac’s classic debut single.

Needless to say, Mac Dre went through his share of drama. In 1996, he was released after being locked up for almost five years for what he maintains was only a playful conversation. For joking about robbing banks. Judging from “Rapper Gone Bad,” being “kidnapped by the feds and treated like a sucker” in the process still haunted him in 1999, even though he tried to be lighthearted about it: “…but now I’m free they see payback’s a muthafucka / I’m sickenin’, like dickin’ all they daughters and nieces / now C.O.’s and P.O.’s want me restin’ in pieces.” But the sheer amount of references to jail make it clear that the time behind bars still weighed heavy on his mind. Not to mention the possibility of being sent up again: “Kinda [para]’noid, they always tryina take your boy back to prison.” It’s no surprise that for Dre a night out would end in jail on this album (“Fuck Off the Party”). In “Global,” undoubtedly a career highlight, the rapper vows to escape the long arm of the law for good:

“I been tryin’ to flip the script and take this rap thing to the next page

but the federalies got me travellin’ on _Con Air_ like I’m Nicholas Cage

Did 4 years, 4 months in the feds but couldn’t get no peace

Released from the belly of the beast but the ‘ralies put a nigga on a leash

The rules and regulations they inflicted had me restricted, paroled

Kept me from blowin’ bomb knowin’ I’m hooked and addicted fo’ sho’

Now how am I to be an MC when I can’t get my travel on?

Can’t bring no babby home cause every morning I’m gettin’ sweated by Babylon

The only way out is to max out and give these fools back they leash

Fuck parole, probation, piss test +and+ supervised release”

At the dawn of the 21st century, a lot has been said about the reciprocity of the terms local and global, but with “Global” Mac Dre delivered one of the most personal, thought-provoking and funny statements I ever came across, giving new meaning to the term ‘global player’:

“Sometimes I sit and reminisce about life in ’87

when I was doin’ my thug game, brain 10 miles higher than heaven

one-track minded, blinded by the game and quick change

not knowin’ across the way-way niggas were doin’ big thangs

And it’s a shame, cause before I hit the f-e-d’s

I didn’t know about them niggas in Cuba and them sisters in Belize

Now I’m curious – is Belizan pussy the bomb?

When they blow do they hum and how quick do they come?

Boy, it’s time to hit the friendly skies and fly like a seagull

post up in spots where the pot’s good and legal

eat tacos in Mexico with cats named Flaco

and catch a red-eye flight the same night to Morocco

[…]

Then bounce to the Phillippines

and get mo’ head than guillotines

Boy, life ain’t nothin but fat checks and head sex

So I’ma get mobile, stay global like FedEx”

In a similar vein, but still different is “How Yo’ Hood?” Over a pointedly East Coast beat, Dre duets with New York representative Killa. Despite several high-profile collaborations on a major label level, “How Yo’ Hood?” remains one of the best bi-coastal rap songs to date because it makes actually sense. The otherwise unknown Killa offers a great verse about the differences between East and West (“We gangbang, it’s just that our slang’s a little different / aim a little different, spit game a little different…”), before they meet up in the third verse.

Another standout track takes us (and Dre) back to prison. “I’ve Been Down” is a compelling narrative delivered in an incredibly intense manner. It’s evident that he really wants you to take a walk in his shoes, to see things like he saw them, as he suggest in the intro. His voice close to a whisper, MD paints a vivid portrait of prison life:

“Bottom-bunk-sleepin’ in a two-man cell

C.O. at my do’ and I’m mad as hell

Punk police, cowboy from Texas

talkin’ some shit ’bout servin’ breakfast

It’s 5:15, he must be psycho

or just plain stupid for thinkin’ I might go

I cussed him out, he gave me distance

but pressed his body alarm for quick assistance

Now these muthafuckas wanna do it the rough way

5 C.O.’s is what it takes to cuff Dre

Straight to the hole but it ain’t no thang

My celly got dank, so I’m Kool & the Gang

[…]

Now I’m chillin’ in my cell lookin’ out the window

drinkin’ pruno, smokin’ Indo

Grabbed my shank, but when I’m finsta bounce

they lock a nigga down for resistance counts

Look at jack books while I’m waitin’

might even do a little masturbatin’

trippin’ off that bitch Dominique

I bust one quick while my celly sleep

Doors rack open, now it’s time for movement

Goddamn pruno got a nigga too bent

Bounce to the movies with my homies

the title sound good but the shit was phony

Damn cigarettes won’t let me breathe

Niggas gettin’ restless, wantin’ to leave

The lights flash on quick as fuck

Somebody in the bathroom just got stuck”

If the rest of “Rapper Gone Bad” was as intense, Mac Dre would have had an undeniable classic at his hands. But in its variety, “Rapper Gone Bad” is still highly recommendable as an introduction to Mac Dre, with artwork and production that could have propelled him past his regional celebrity status. On the musical side, Lev Berlak & Will ‘Flexxx’ Hankins cover a wide spectrum with the minimal funk of the title track (with added old school flavor courtesy of Malcolm McLaren and the World Famous Supreme Team), with the melodical “Fish Head Stew,” the stutter-stepping “Fortytwo Fake,” the trunk-rattling “Fuck Off The Party” and the melodramatic “Mac Stabber.” Warren G brings his updated G Funk to “Fast Money,” Tone Capone is his usual reliable self on “I’ve Been Down” and “Fire,” while Phil Armstrong showcases mob music’s superior use of keyboards on “Global,” “Valley Joe” and “I’m a Thug.”

On the latter two, Mac Dre hooks up with fellow V-Town rappers. “I’m a Thug” features PSD and longtime partner Dubee, while “Valley Joe” unites rival turfs Hillside (B-Legit, Lil’ Bruce) and Crestside (Mac Dre, PSD). A third track concerning local matters is “Mac Stabber,” a simultaneously brilliant and bitter moment on “Rapper Gone Bad,” which sees Dre attacking Mac Mall with surprising vengeance, catching another prison flashback: “That nigga left me for dead when I was doin’ time in jail / couldn’t shoot a nigga naythin’ when he was havin’ major mail.” It’s a diss track as venomous as they come. Who knew that there was so much drama behind what looked like business as usual? At a time when rap fans are fed mostly industrialized beef, it’s hard to see the personal dimension of this song. One needs to realize how hard Mac Dre and Mac Mall both represented their Country Club Crest neighborhood throughout their careers to realize the viciousness of a line like “Chump, where the fuck you from?”

Mac Dre was never markedly compassionate or introspective, but from what little was revealed in this review it should be evident that he was an intelligent rapper with a lot on his mind. A true funkateer, Dre liked to strut his stuff, but combined the flamboyance with craftmanship. He was a prime example of the Bay Area’s self-sufficient rap scene, who’s been known to bring forth some of the most original MC’s to ever touch a mic. When he admonished rappers, “keep it real, dog, and represent what’s right / be a real hog when you bless the mic,” these were words he lived up to himself. Mac Dre understood the rules, right down to how fast they can change: “How can a bullet-proof vest protect my wig? / See, them cutthroat fools done changed the rules / The public got it twisted and we blame the news.” You can mark Mac Dre off as another ‘gangsta rapper’ who had it coming to him, but that would probably be as far removed from the truth as possible. To use a term not often applied to West Coast MC’s, Mac Dre was also a ‘rapper’s rapper’, loved by the people, but especially estimated by his peers. With his tongue-in-cheek demeanor he represented a most revered circle of rappers that includes legends like Slick Rick and Too $hort. He mastered many flows and could interact with a track in a way rappers in other places (New York, specifically) were just beginning to get hip to. He was proud to be old school “like Grandmaster and the Five that was Furious” at a time when anything older than five years was already considered old school. He had almost everything you look for in a rapper, the style, the slang, the storytelling ability (“Fortytwo Fake”) and the personality. Despite an inconsistent body of work, he’s been present in three decades. In this reviewer’s opinion, the skit-free and all-exclusive “Rapper Gone Bad” is one of Mac Dre’s best full-lengths, speaking loudly of his dedication as an artist.