Let’s have a look at a little known experiment that the music industry was running between the later 1990s and the later 2000s. If that sounds in any way conspirational, it absolutely isn’t, it’s simply me connecting dots that cursory rap listeners probably have missed at the time. For record buffs it goes without saying that this article couldn’t have been researched without the database Discogs.com.

In order to market American artists abroad, some labels began to add local MC’s to existing songs and release these enhanced tracks exclusively in the guest’s home country. Def Jam Records was pushing these efforts once it had the international pull as part of Universal’s The Island Def Jam Music Group. This corresponded with Def Jam’s long-held ambitions to open up local chapters, which they did first with Def Jam West in 1992, then, most successfully, with Def Jam South in 1999, and at the start of the millennium with Def Jam Germany, Def Jam Japan and Def Jam UK.

Researching these features takes time and luck, so there’s a good chance that I may not have caught every single one, especially in the Eastern Hemisphere. To make it clear, these are almost throughout not personal collaborations between individual artists (or real remixes) but hybrid recordings concerted by label employees that serve different marketing purposes. They provide an additional incentive for customers to buy a single or for disc jockeys and station programmers to play a song. They stroke a domestic audience’s ego by acknowledging the existence of native artists and letting them join a single of a major US star. Finally they support the global music player’s local efforts, which may comprise the career of the featured rapper signed to them.

The first such release that I took note of was “Affirmative Action (St Denis Style Remix)”, a French version of the 1996 Nas song “Affirmative Action” from his sophomore album “It Was Written” that was also the formal introduction of supergroup The Firm. The remix featured famed French rap duo Suprême NTM. AZ still opened up the song, while NTM took the slots of Cormega and Foxy Brown. This combination was as high profile as could be. It had its own video, footage showing Joey Starr and Kool Shen on the same set with their host. On Nas’ part, it may have added an international flair to his Firm concept, on Columbia’s part, it was a successful effort to bring together the world’s most important markets for rap music that deserved its own video budget. Because back home (and in the rest of the world), while remixed in a way to align it with the perceived pinnacle of all posse cuts, the Juice Crew’s “The Symphony”, and equipped with all-new lyrics from the Firm members, “Affirmative Action” was only the b-side of the “Street Dreams” single.

1997 produced two entries that were remixes in the traditional sense (same song, different music), tellingly in the R&B genre. Norway’s production linchpin Tommy Tee planted N-Light-N on his remix of Alexander O’Neal and Cherrelle‘s “Baby Come to Me” and Italian duo Sottotono cleared out Nas and the Jimmy Jam & Terry Lewis beat on Mary J. Blige‘s “Love Is All We Need”. Arguably one of the strongest catalysts for rap and R&B joining hands (although many others came before her), Mary J. released at least one other foreign version when France’s Lady Laistee substituted Common on “Dance For Me” in 2002. (She was also on a belated reworking of a 1992 En Vogue song, 1999’s “My Lovin’ (The B.O.S.S. Remix)”.)

But back to Nas. In 1999 another of his singles was modified with international guests. “Hate Me Now”, a certified comeback for Nas in the form of a payback that had Puff Daddy taunting haters at the top of his lungs. Now there were two remixes for two different countries. Afrob in Germany and Frankie Hi-NRG in Italy, the former a notable Afro-German representative, the latter an Italian pioneer, performed on their respective remixes according to their individual disposition, Afrob speaking up four times to echo Nas’s sentiments, Frankie (without dropping an actual verse) repeating his own extended chorus that culmiantes in ‘If you hate me you kind of hate yourself’ – both more or less bumping Puff off the track.

Also in 1999, WEA released Missy Elliott‘s “All N My Grill” as a single in Europe, replacing the album cut’s cameo, OutKast’s Big Boi, with longtime French flagship rap star MC Solaar. (Meanwhile in the US, the Missy single to be loaded with extra rappers was “Hot Boyz” featuring Nas, Eve and Q-Tip – while I vaguely remember allegations of Missy dismissing her European co-star.) The same year the Mack 10 feature on Warren G‘s “I Want it All” was swapped for Alliance Ethnik’s K-Mel for the single put out by BMG France. And independent hip-hop’s most notorious single that year, Pharoahe Monch’s “Simon Says” was remixed by London’s Skitz, who brought countrymen Rodney P and Roots Manuva along.

In 2000, the idea was exported to Japan with a remix of L.L. Cool J‘s “Queens Is” featuring Dabo. The next year, the UK became involved on the major level with Ms. Dynamite and Maxwell D guesting on Ludacris‘ “Southern Hospitality”. And the concept of multiple national versions was expanded beyond the two (known) remixes of “Hate Me Now”. Possibly the rarest physical item in this list, early 2001 saw the release of Wu-Tang Clan promo records for the song “Careful (Click, Click)” which contained 5 different versions – the ‘Firestarter Mix’ with Kardinal Offishall, the ‘Alles Real Mix’ with Curse, the ‘Brown Panthers Mix’ with Che, the ‘Twang-Vs-Tang Mix’ with Blak Twang and the ‘Le Rat Remix’ with Le Rat Luciano. Only the German and the Canadian variants were further exploited, one as a CD single, the other as a CD bonus track.

Outside of the very specific marketing scheme described here, the method had been long effective for R&B tracks that were reedited with rap cameos who were meant to bring star power and a street edge to a track (technically not the same as sung songs presented in alternative versions that only differed from each other in respect of the rap part being present or absent, but practically amounting to the same thing). So it was nothing out of the ordinary when domestically Def Jam in 2003 equipped Ashanti‘s “Rain on Me” with Charli Baltimore, Hussein Fatal and Ja Rule, while the “Rain on Me (Taz & Vanguard Remix)” featured Taz, apparently the only rapper ever signed to Def Jam UK.

At the beginning of the millennium, Def Jam Germany was eager to sign Kool Savas, a cocky underground spitter on the verge of becoming one of the dominant MC’s of his country. He joined BMG instead and wound up on German versions of Cassidy feat. R. Kelly’s “Hotel” (2003) and T-Pain‘s “I’m Sprung” (2006), both opportunities for him to promote albums from his camp. He also made Jadakiss feat. Anthony Hamilton’s “Why” (2004), whose US remix was shared by Styles P, Common and Nas. He developed an actual working relationship with Lumidee (best known for her hit “Never Leave You (Uh Oooh, Uh Oooh)”) after joining her on “Crushin’ a Party (2003)”, which, unlike the original with Noreaga, was commercially released as a single. These R&B and mainstream rap features enabled by the majors were a clear break for an artist who had teamed up with Rawkus act Smut Peddlers (The High & Mighty + Cage) in 2001 for “That Smut Part 2”.

But back to Def Jam. Another one of their R&B singles (on sublabel Def Soul), Christina Milian‘s “Dip it Low”, geared up for world domination in 2004. Already available with gender-separate mixes featuring Fabolous and Shawnna and a ‘Coast to Coast Mix’ with Fabolous, Jadakiss, Snoop and Nate Dogg, further versions were targeting local markets such as Germany (Samy Deluxe), Japan (S-Word), Russia (Detsl), Taiwan (Will Pan), France (Lynnsha – a singer, not a rapper) and the Latin world with the ‘Reggaeton Remix’ featuring Puerto Rican Julio Voltio.

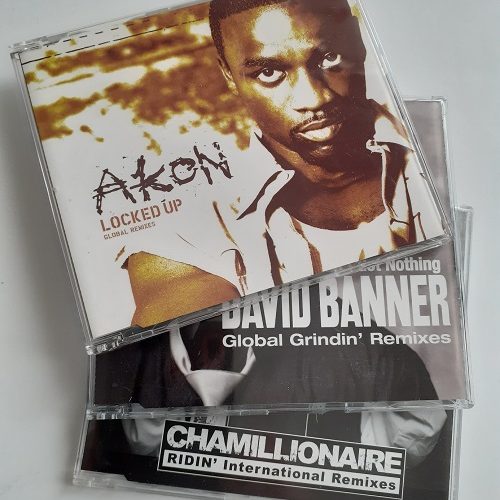

In 2003, Akon was a prospective in some sort of crossover category (as a global citizen in the vein of Wyclef Jean compatible with both rapping and singing), and he immediately lived up to the expectations. “Locked Up” wasn’t his debut single (that was “Operations of Nature” as A-Kon in 1996), but it launched his international career. As if anticipating his breakthrough, the version of “Locked Up” with Styles P was followed by an entire series of ‘Global Remixes’ (which was the subtitle of one pressing, also released under “Global Lockdown: The Locked Up Remixes”). Styles had originally been alloted two verses, on the UK remix the first verse was assigned to the previously mentioned Taz, who had a jail tale of his own ready. The German version omitted P and had instead two verses from Azad, Germany’s longest serving hardcore street rapper, who also imagined himself behind bars. (On a related note, to promote the ‘Prison Break’ TV series in Europe urban artists were enlisted for ‘theme songs’ for their respective countries, the most successful being “Prison Break Anthem (Ich Glaub An Dich)” with Azad.)

New Zealand delegated Savage, who raged with fervor against his imagined incarceration (“I wish I could break these walls and bend these bars / find myself with bitches in a Bentley car / Tryina find out who dealt these cards / I don’t see my dreams happening in these yards”), France Booba, who would soon ascend to 50 Cent heights with his brand of commercial street rap, Canada Mayhem Morearty, at the time a hopeful with a Saigon-like poise who in real life wound up testifying against a deranged rap partner who went on a killing spree, and Puerto Rico again Julio Voltio.

The repentant gangster ballad over glossy production did not only jumpstart Akon’s career, it became one of the hallmark songs of his career, especially in view of the often questionable quality of the rest of his output. “Locked Up” has an artistic legacy that “Lonely” and “Smack That” don’t have, let’s put it that way. Early on in 2005 the incarcerated C-Murder released his rendition called “Won’t Let Me Out”. The song’s run unexpectedly hit a low point last year when rap troll 6ix9ine opened his post-jail album with “Locked Up Pt. 2”, joined by the man himself but ignoring the template set by Styles P et al. by singing his part. While 6ix9ine crooning/croaking alongside Akon to tick off the token ‘prison song’ should be the nail in the song’s coffin, back in 2006 Akon should have been recognized for putting Dutch artists Ali B and Yes-R (cousins with roots in Morocco) on the remix for the exlusive “Ghetto” single.

Columbia (Sony) didn’t abandon its strategy of international features, again with Nas in 2002 when Dutch MC Brainpower shared “One Mic” with the Queens legend and in 2005 when the ever-ambitious Rohff from France stood in for T.I. and Lil Wayne simultaneously on Destiny’s Child‘s “Soldier”. Meanwhile, Atlantic (Time Warner) put Sweden’s Chords and Timbutku on T.I.‘s “Why You Wanna” in 2006. You would think Scandinavian features would be easier to find, but you really have to dig for them, such as Denmark’s Majid sneaking onto the ‘Saqib Remix’ of City High‘s “Caramel” featuring Eve in 2001.

The largest record company in the world, Universal, followed suit via its SRC Records subsidiary. In 2005 they copied the Akon recipe with multiple remixes for David Banner‘s “Ain’t Got Nothing” with the ‘Global Grindin’ Remixes’. The highest profile combo were Canadians Kardinal Offishall and Solitair, two of Toronto’s finest from that era. The double features continued with Rodney P and Durrty Goodz in the UK, Lino and Treiz in France, Samy Deluxe and Eddy Soulo in Germany and Savage and Tyree in New Zealand. The only David Banner song to chart overseas was “Play” who snuck into the UK top 100 for exactly a week, but “Ain’t Got Nothing” earns the distinction of having the highest density of foreign features here. The fact that too many sensitive words are censored is made up for by Banner introducing his guests on each version except for the French one.

One year later Universal had a hit at their hands that really reverberated almost around the globe – Chamillionaire‘s “Ridin'”. As a very specific song that deals with racial profiling (essentially the street precursor to “Hip Hop Police”), it was an unlikely pop success to begin with, remixes with foreign MC’s could accentuate the problem even further – or instead argue for a universal relevance of the song. Adding to the challenge was that Cham’s original duet partner, Krayzie Bone, was an essential part of the song. New Zealand candidate Tyree made the best out of that dilemma by not replacing Krayzie but the host’s second verse and sticking closely to the script by denouncing the police’s efforts to catch him riding dirty, quipping, “It’s embarrassing / Anybody would think you five-o’s are groupies the way that you’re harassing me”.

The UK’s Sway goes into his usual chipper tone but manages to swerve by Houston: “On this side of the ocean we don’t cruise, we move quick, there’s a lot to do / Indeed my click run up in your crib so quick it’ll make techno sound chopped and screwed”… Germany’s Olli Banjo slows down and speeds up his flow, which could also be a nod to the song’s origin, but focuses on its show-off aspect. France’s Al Peco connects with Koopa on a different level, asserting that they both ‘deal hope in the ghetto streets’. We’d have to speak Croatian to understand what Bolesna Braća‘s Baby Dooks and Bizzo have on their minds apart from repping Zagreb (that much we understand), but they are no strangers to crossing the Atlantic, Dooks being an associate of Koolade and Dash with production credits for Masta Ace and Masta Killa. Finally Cabal, from “the place where every chick’s like Gisele [Bündchen]”, inserts English bits into his Portuguese in “one take, no rehearsal / same label, rap is Universal / Bra’ hip-hop e gringo loco / rollin’ hard and fuck the po-po”. By the way, the ‘universal’ aspect of “Ridin'” was further underlined by official mixtape versions with Bun B and Pimp C, Jae Millz and Papoose, and DJ Quik and The Game.

What is a natural, actual collaboration and what is not? It’s not always possible to draw a clear line. The public sometimes has this romantic notion of artists working together in the studio or at a remote ranch in Wyoming. True, there may be a difference between hopping on a remix and being put on a remix, but many of the people who typically work on a recording don’t even share a professional relationship. Sure, if the same guests would have been – and some may have – opening acts for the same stars, that would entail a hint of prestige that these combinations are devoid of. Still this unsual form of music promotion facilitated ‘features’ that otherwise wouldn’t have been possible.

There’s always an edge where a good idea gets pushed over the brink into the abyss of absurdity. The most pointless ‘remix’ I found dates from 2002 where German anglophone rapper Raptile joins a Canadian allstar cast under the direction of Ghetto Concept for the BMG-devised “Still Too Much (German Mix)”. Speaking of Germany, the saddest possible combination in this context must have been pop rapper Der Wolf being dumped on the Big Daddy Kane single “Hold it Down”, a track from his last and obscure album.

In turn, the Warren G/K-Mel combo creates the illusion of a bonafide collabo because there’s a part where Warren says his new guest’s name. Brainpower is one of the few to actually re-mix a song he provides vocals to, 2004’s “Triple Trouble (Brainpower Remix)” by the Beasties, and like Suprême NTM he managed to bump fists with Nas in front of a camera in the case of “One Mic”.

Maybe, 25 years later “Affirmative Action (St Denis Style Remix)” is still the shining example that hasn’t been eclipsed. But just because most of these tracks were ignored doesn’t mean that they can’t make sense. Especially the “Locked Up” versions absolutely make good on the promise, all adding a local perspective in the spirit of the original rap version with Styles P, even as we are aware that they tread the fantastic cosmos of gangsta rap.

Regarding the opportunity to build a unique global hip-hop brand, Def Jam Germany never attained any credibility and shut down after two years, Def Jam UK had exactly one rap signing but a dozen compilations by hip-hop monopolist Tim Westwood. Def Jam Japan seems to have given some attention to the careers of Dabo and S-Word but also seemed to consider the Teriyaki Boyz the end of its efforts. Only Def Jam France was successful over an extended period, but didn’t start until 2012.

The period covered by these audio montages coincided with hybrid forms of so-called urban music gaining an international dimension with (yet singular) crossover successes from reggaeton and grime and acts with a global appeal such as M.I.A., Gorillaz, Gnarls Barkley, N*E*R*D. etc. The international network of hip-hop artists and activists however goes much deeper and we’ll get to some of its aspects in the future. So consider this post a footnote for a phenomenon that wouldn’t even be a footnote if one didn’t compile all these bits as I’ve done here.