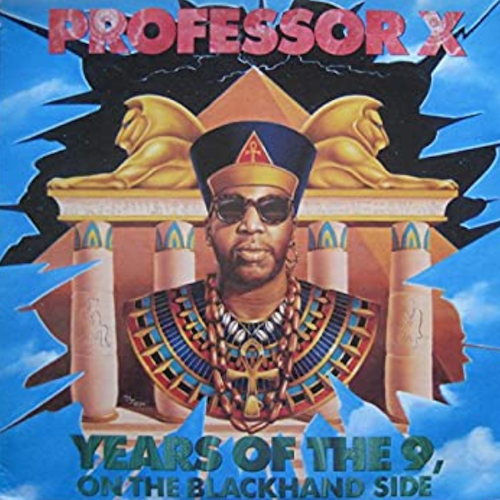

If you’re going to talk about Lumumba Carson a/k/a Professor X you should always put respect on his name. The son of political activist Sonny Carson, Lumumba would become an activist in his own right, although he would make his mark through hip-hop music and culture. As a founding member of X-Clan and a leader in the Blackwatch Movement, Carson took his father’s torch and carried it forward to the youth. At the peak of their prowess in the late 1980’s and early 1990’s, both X-Clan and Blackwatch were part of what was dubbed the “Afrocentric era” of hip-hop. There was a thirst to learn about black history both here and in the motherland of the African continent. X-Clan and Carson were there to quench it.

It wasn’t long before those who feared black nationalism tried to put their own negative spin on it. Professor X was called everything from “racist against whites” to “antisemitic,” and he did not back down from any of his critics nor change his words. Whether you agreed or not with X-Clan rapping about “cave dwellers,” he wasn’t changing his tone or words any more than his father had. In fact he couldn’t have had a better example for sticking to your principals in the face of adversity than Sonny Carson, who had been sent to Sing-Sing on trumped up kidnapping charges for 15 months as a young man. Lumumba Carson was never going to let any devil get on his level and tell him what to do.

It couldn’t be any more clear how Professor X felt on “Years of the 9, on the Blackhand Side” than on the intro to “Gorillas in the Mist.” To quote the late Mr. Carson: “There has never been a movement, where the leader has not suffered for the cause, and not received the ingratitude of the people.” Let’s focus on two words in that sentence — “suffered” and “ingratitude.” For Professor X this is a righteous cause, one for which he refuses to be bowed or broken, one which he is prepared to suffer any indignity for if it leads to the betterment of black people. In doing so he acknowledges that even in the African-American community, his noble sacrifice may not be cherished. “Ingratitude” means “without gratitude” or “thankless,” and X is prepared to go as far as it takes to achieve his goals, without any praise or adulation from any individual or group. In fact it forms the core tenet of his cause. He would rather do it because it’s the right thing to do regardless of receiving any accolades — they would cheapen the value of that which he stands for.

“What’s up G? I don’t mean the currency/or even your fly girlie.” Carson refuses the trappings of material wealth or even the prospect of female companionship on the single “What’s Up G?” He wants to elevate himself and his listeners to a higher plane of consciousness. “Of these degrees I shall use a quarter/to bring African back to your order.” It is a noble task that Professor X has set for himself, one that should be respected in the light of his suffering and the ingratitude he received, but not one that should be exempt from criticism solely due to his sacrifice. It is a STRANGE song. In the X-Clan it was always Brother J who put forth Blackwatch Movement’s ideals and values in rap form, because with all due respect, Professor X is NOT a rapper. Hearing his lilting voice attempt (and fail) to flow over an awkward combination of funky drums and bluesy harmonicas leaves little doubt rapping is not his forte.

At times “Years of the 9, on the Blackhand Side” is a pretentious album. Carson clearly knows he can’t rap, but he’s been emboldened by the media attention he and his cohorts have received, so he tries his best on songs like “Call a Spade a Spade” anyway. I’m not sure I can call it a good “rap” song. It’s set off by a deejay’s scratch, it’s got a head nodding track with strong bass, and it’s easy enough to listen to. One can even say he’s rhyming on the track, but he’s not rapping to the beat. He’s simply reciting lines at his own pace, exhorting words for emphasis where he likes, and letting a singer come in periodically to give the presentation a hook. It’s spoken word poetry wrapped up in the trappings of 1990’s hip-hop instrumentation.

The peak of the oddity here may be “Ahh!” The song’s very title recognizes the fact that Professor X is known FOR his exhortations — the trademark way he says phrases like “Ahh!” and “VANGLORIOUS!” You couldn’t be a fan of the Clan and not expect him to say “This is protected by the red, the black, and the green… WITH A KEY!! SISSY.” That’s part of the package and one that comes with the presentation. It’s charming and fun in small doses. Trying to extend it for the length of an entire album, no matter how funky and fresh the production, proves that he’s meant to be the leader of a movement and not the rapper FOR the movement. By the album’s conclusion on the Grace Jones inspired and new jack swing styled “Pull Up to the Bumper” there can be little doubt the gimmick has run its course.

I hate having to rag on a deceased man who I clearly admired and respected for his work during his lifetime, so I’ve tried very carefully to paint the whole picture of what “Years of the 9, on the Blackhand Side” is. I think at some point Lumumba Carson briefly forgot about his purpose and wanted just for a moment to be held in the same regard as Chuck D or Ice Cube as a rapper. That’s fair. Who wouldn’t want to be at this time in hip-hop music and culture? Sadly he couldn’t pull it off, but it’s certainly an interesting record in retrospect, one filled with knowledge of self and black pride along with an incredibly stilted and at times painful lyrical delivery. It certainly doesn’t commit the cardinal sin of being boring. R.I.P. Professor X.