These days, I suspect it’s easy to learn about most things, but I’m still stuck when it comes to Art. I say this humbly, but also critically – in poetry, there’s almost no good criticism in print, or online; in Classics, there is just a mechanical sense of nuance, and, to many, no explicit value in slow (and painful!) language acquisition; in hip-hop, there is a strange lack of biographical material and detailed stylistic surveys or commentaries, especially when it comes to quality rap. Minus a few obscurities, rap hasn’t received its “grand commentary,” a synthesis into the world’s artistic tradition — that is, at least not stylistically, not as a complex art in its own right, taken on its own terms, in the context of its own tradition. A paradox? Perhaps not, as it’s inaccessible to most, a strange misfortune for the talented, or at least the very earnest.

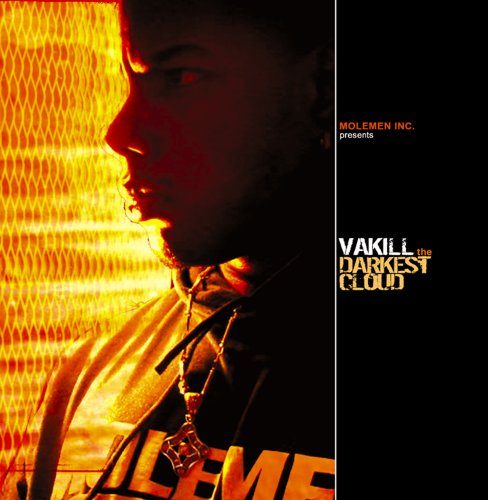

And such is the case of Vakill, a Chicago rapper that’s been around since 1995 on a few demos and compilations, gaining some marginal attention only in 2003 with “The Darkest Cloud.” Still, despite his increasing visibility, there’s almost no information available on the guy. Google searches come up with positive results, but most of them are internet discussions linking to the same couple of interviews; reviews exist, but they’re mostly on Amazon or Epinions, with only a handful of professional sites or magazines ready to declaim; and clicking on his lyrics on those mutually-plagiarizing lyrics websites is like enthusiastically searching for a dead end, textless and alone. But, does his work warrant the search, or even the attention? In short, YES, with ample reservations — and here’s why.

As the first song winds down, a few things become obvious. For starters, it’s a dark and sometimes grim album, an artistically neutral observation but a personal bias of mine: I like gritty, dark introspection, provided it’s done well. The production on the title track is unspectacular, but makes good use of an electronic “groan” against some light, ominous strings, a fine if unoriginal backdrop for battle rhymes. No humor, but frequent distinction, and occasional leaps to greatness — consider this the norm for much of the material here. And Vakill is quite the self-conscious (not conscious) rapper — that is, he knows how to craft a great line or verse, and recognizes his own artistic value, recommending himself as a top-ten emcee at least once, perhaps on the spate of his curdling wit:

“Call my style ‘c-section

‘Cause I’m a cut above you pussies!”

“And the judge will sentence me so many times

He’ll have to indent the shit and put it in stanzas!”

The main attraction here is lyrics. He has some of the best one-liners I’ve ever heard, and truly quotable rappers are rare. He does not compromise his verses, either — many are uniformly good, with enough variation to buck the crippling monotony that hurts so many other artists. Still, although Vakill’s style is distinctive, it’s unoriginal, an admittedly clever mix of “sex and violence / vocabulary and science / – in an uneasy alliance!” ( Ras Kass, “H2O Proof”) and the perfunctory sexism, and wacky politics (more on that later). Although his delivery is good, it’s never great. Too often, Vakill sacrifices nuance and expressive intonation for speed and intensity, especially on the battle tracks. It’s certainly not unimpressive to the ear, and perhaps even appropriate for the content, but he’s simply not an elite performer, like Ras Kass and the Notorious B.I.G. were. He lacks the expressive pauses, the occasional sarcastic jab — it’s like Vakill honed his voice as aweapon, not a well-rounded artistic instrument. Fortunately, he slows down for some of the conceptual material, like in “The Creed”:

“I granted my neighborhood immunity

during the Rodney King riots

when niggas burned down and looted they own community

Instead, I pulled bricks from the walls of my imagination

and threw them through the window of opportunity”

Here, Vakill is more expressive, and a bit more subtle. Still, the track’s understated piano is far too similar to the former’s strings — sure, it’s driven towards a different purpose, but melts too quickly into the first track, especially on the first few listens. Again, the music functions well against his voice, but has little distinction, and, perhaps, offers itself as a mere prop. That’s a solid performance on Molemen’s part, but just dabbles in potential, and that is all. But, on lyrics, as well as song structure itself: how does the conceptual stuff hold up against his battle rhymes? Above, it’s a set-up: an examination of racism and poverty, which avoids sappiness, although the unequivocally great opening degenerates into frozen incongruity in the second verse. Yeah, it still drips Vakill’s characteristic wit and technical feats, but it’s a bit apart from the conceptual narrative he had going at the start:

“Ho’s is like tornadoes — they scream when they come

and take everything when they leave

I give a bitch a warm reception instead of fur

And if the crazy notion of marriage in my head occur

and lawfully wedded her

It’s all good — wife’s an acronym, for Wash, Iron, Fuck, Et cetera”

Is this a unified concept track, or something else? Sure, it could be “both,” but then each incongruous part is glued together at the expense of the other. So, here’s the problem: “The Darkest Cloud” is technically excellent, but rarely (1, perhaps 2 tracks, and a couple of scattered verses) great. The former’s rare, but the latter even rarer — for example, it’s the manifest different between “The Creed,” and the Juggaknots’ “Clear Blue Skies.” Both are far beyond most rappers’ talents, but one is even more than that — an unequivocal statement, unified, not glued, by something simultaneously tangible and transcendental. Musically, it’s a tender fusion of horns and muffled screams against a surreal, atmospheric narrative, a total package, a sum. “The Creed,” though… not a sum, but a collection of well-wrought, titanic parts that grind much, but harmonize little.

“Forbidden Scriptures” boasts one of those corny titles, but still delivers. Not about anything in particular, really, but has some of the best battle verses on the album. In fact, four of them are delivered by other artists, three of which — Copywrite, Jakki da Motamouth, and Camu Tao — are actually quite talented, at least here, and rival Vakill’s performance at the end, and have better flows. Jakki’s lisp (now lost, unfortunately, as far as I can tell) paradoxically works to his favor, especially when he loads the sibilants on the tongue.

Next up, “American Gothic” — the beat’s too gothic, driven by a single organ and a sitar, both of which are spectacularly dull. “Spectacularly,” because the combination appears interesting on paper, but the sitar just sort of rings there, chronically unexploited and underused, a throwaway, perhaps, to distract from the sloppy organ. In short, no surprises, as the track ends up sounding too much like its title; it’s one of the worst things on the album. And, perhaps it’s a self-inflicted handicap (or not!), but I’ve pretty much trained my mind to draw blanks at perpetual references to Allah, the anti-Christ, Nostradamus, and other pop New-Age-meets-the-ghetto fluff-jobs, especially if it’s all packed into the same verse, like a parody of itself, and has little wit to redeem it.

In contrast, “Forever” deserves special mention for its production. Just like “American Gothic,” it’s driven by an organ, but consider the differences: start-stop pauses, with a healthy sprinkle of variety. A distinctive drum, a horn, and a sharp, muffled scream, all well-timed and carefully apart. No drowning, as Vakill’s speed brings out the background quite well.

Although “The Darkest Cloud” is generally quite promising, two tracks stand out in particular. “Sweetest Way to Die” is a near-great conceptual track, detailing a young enthusiast’s (perhaps Vakill?) life in golden-age graffiti. Musically, it’s one of the best things on here, as the beat works expressively to punctuate Vakill’s flow: vast, epic horns signal scenes and dramatic pauses, while the sound itself is faintly nostalgic. And, the magic’s quite known — slow things down a bit, let the instruments echo each other, and there it is: “time,” or, its abstract invocation. I suspect Vakill’s references to “toys” and “black books” help, too — he recalls and magnifies 1980s hip-hop culture, and one scene stands out especially as an example of artistic self-control:

“- Yo, call your shit nigga.

– I got yellow in the corner, dude. What’s up with this tagging bullshit, dude?

– I’m sayin’ man, I ain’t sweatin’ this shit…

– You ain’t makin’ no money off that punk shit, dude…

– Yo, it ain’t about the dough, it’s about hip-hop…

– Dude, you lookin’ like shit with paint chips all over your fuckin’ legs…”

Note the unforced character of the conversation — what can easily turn sappy and too self-conscious is kept alive with humor and spontaneity. Although it ends too abruptly and has only a perfunctory sense of “closure,” it sticks out as the best conceptual track on the album. Similarly, “End of Days” is the best battle track on the album — it has the same start-stop, jerky feel of “Forever,” and the sharp instrumental variety that marks the album’s best material. It also helps that Vakill delivers the most quotables per square inch of song:

“Competition is like parking spots —

Good ones hard to find

And everything else is handicapped!”

And the above could have, and should have, made a genuine classic. As it stands, Vakill produced a very good debut with two or three tracks too many, not enough polish on some of the conceptual material, and a few weak beats. But, judging by his Molemen compilation in 2000, as well as his follow-up, “Worst Fears Confirmed,” Vakill, although inconsistent, has a lot of good material. Still, he needs to push himself to greatness, which is both difficult, and impossible: from my experience, artists “get it” or they don’t, and Vakill, at this point, is monstrously capable of both.