Now… I’m 39, right? And I still love rap music. I love rap music, man. You know. I love it.You know, I’m 39, I’m that age, man. I’ve been loving rap music forever. And as I get older I realize I’m gonna love rap music when I’m 80, 90. Now I love rap music, but I’m tired of defending it. Cause you gotta defend rap music, man. Cause people always go, “That’s not music. That’s not art, that’s garbage. How can you listen to that garbage? How can you listen to that trash?” And in the old days it was easy to defend rap music. It was easy to defend it on a intellectual level. You could break it down intellectually why Grandmaster Flash was art, why Run-D.M.C. was art, why Whodini was art and music. You could break it down. Intellectually. Okay? And I love all the rappers today, but it’s hard to defend this shit. It’s hard, man. It’s hard to defend “I got hoes in different area codes.” On a intellectual level. It’s hard to defend “Move bitch, get out the way.”

(Chris Rock in 2004)

The average rap fan knows what it’s like to have to defend rap music. Whether your tastes are questioned directly or you happen to walk in on a discussion, you’re liable to deal with everything from serious concerns to outright slander. Personally I have stopped defending rap and everything that goes with it. Occasionally rap needs to be explained, and if properly asked, I try my best to explain it. But defend it or even defend myself for listening to it? I flat out refuse to enter any such argument, simply because I find the ignorance that demands me to defend it more annoying than any ignorance I might encounter within rap.

That being said, I’m fully aware that rap often winds up needing justification, and that sometimes acquittal and absolution are hard to come by. Some rap is hard to excuse, even when it can be explained. The Convicts album is a case of rap crossing a certain line to the effect that any defense strategy becomes pointless. Nevertheless it has its share of supporters, some of who choose to put it on a particular pedestal. More recently, it has been called ‘a testament to the genius of ignorant rap’ (Unkut.com) and an ‘outrageously ig’nant rap masterpiece’ (HipHopDX.com). Or, more neutrally, ‘one of the most aggressively ignorant records from an era when Rap-A-Lot did nothing but put out aggressively ignorant records’ (Complex.com).

When dealing with the term ‘ignorant rap,’ it is important to understand that it has essentially two functions. It was conceived by people who love rap but can still laugh about it (and make us laugh about it, just like Chris Rock), basically an invention of rap nerds (’90s magazine ego trip had an Ignorant Rhyme of the Month feature). Of late, it has also been used as the antipode to so-called ‘conscious rap.’ Nobody celebrated ignorance in rap 20 years ago, it was the pretension of ‘conscious rap’ advocates that provoked some rap fans to stand up for music whose consumption they felt wasn’t necessarily to the detriment of its audience.

While I appreciate the sentiment, various issues arise when ‘ignorant’ is applied to rap as a term of endearment or even a mark of excellence. One is that a supposedly ‘ignorant’ creation is beyond criticism. Because either the artist was purposely ignorant or he simply didn’t know any better. Or is it in any way plausible to rate ignorance in art based on the degree of artistry? If so, is sharp, elaborate ignorance still ignorant? Supporters of the label ‘ignorant rap’ do have one point – self-appointed guardians of the ‘right’ kind of rap often dismiss artists based on the slightest trace of ignorance. But in turn championing artists or albums as ignorant is nerddom at its most… ignorant. (Or is that a paradox as well?)

Never ignorant, RapReviews.com always looks at the full picture. So, in honor of OG Style, let’s note that Rap-A-Lot Records did have other things on offer. Of course there’s a certain exploitive pattern to Rap-A-Lot’s early ’90s output, but summing up “Mr. Scarface Is Back” or “We Can’t Be Stopped” as ‘aggressively ignorant’ is not even half the story.

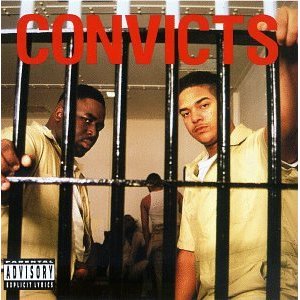

So what about the Convicts? Consisting of Lord 3-2, straight out of Houston’s Hiram Clarke neighborhood and Big Mike, a New Orleans native who had been introduced to Rap-A-Lot by Tony Draper (later head of Suave House), Convicts were a concept group put together by the label. As mentioned earlier on this site, it was a transition time for the up-and-coming company as it discovered a winning formula of street themes and shock effects. Several songs on the album indicate that the Convicts for instance were originally called Ex-Convicts. But if you want to attract attention, what’s more immediate, realistic, controversial – cons or ex-cons? Still 3-2 and Mike indiscriminately switched between both.

We begin with the parole hearing “Free World,” during which they of course thoroughly ruin any chance of being paroled. “Penitentiary Blues” finds Mike lamenting his fate from behind bars, complaining about court appointed lawyers, nasty inmates, a cheating girlfriend and a shortage of smokes. “I Ain’t Going Back” starts out normally enough, 3-2 trying to get a job. But soon enough he winds up shooting his parole officer and is on the run, resulting in lots more casualties. “DOA” is a similar killing spree, Big Mike first getting back at a lover, going to jail for it, and returning with yet more names on his hitlist. “Peter Man” is his dope tale, a turf rivalry with a bloody ending. Wanting to appear smart, he drops lines that somewhat contradict his status as a Convict: “Although I’m the man I’m not the one to take a chance / for the penitentiary by sellin’ out of my hand / Cause everybody knows I’m no goddamn dummy / So I get somebody else to sell this shit for me.”

Apparently the ones to give advice, they set up a hotline for aspiring criminals, “1-900-DIAL-A-CROOK.” Admittedly one of the most stunning songs in Rap-A-Lot history, it makes full use of the label’s talents, from a Hispanic-accented Scarface calling in because he’s looking to “steal a Cadillac down the street” to Big Mike providing him with exact instructions on how to break into the car and start it, or 3-2 doing the same for the Jamaican tired of selling weed who’s interested in learning how to cook crack. In best Rap-A-Lot tradition, things take a bizarre turn when (inspired by the Gulf War) label owner Lil’ J calls from Saudi Arabia inquiring how to take out Saddam Hussein and Willie D and Bushwick Bill gladly chip in, despite the fact that in the same year they would put out a song called “Fuck a War.” If you remember the hunt for Saddam in 2003, you’ll also be prompted to double-check the release date when Will says, “You can’t use a scope like the old days / cause the motherfucker hidin’ in them caves.” Complete with beat switches between each segment, “1-900-DIAL-A-CROOK” is a masterpiece of theatrical rap and far superior over the 2000 Roc-A-Fella track it inspired, “1-900-HUSTLER” (from “The Dynasty”).

Speaking of inspiration, “Fuck School” casts a light on the connections between Rap-A-Lot and Death Row. Not only was Bushwick Bill on “Stranded on Death Row” and did Snoop shout out the Peter Man on the same song, “Lyrical Gangbang” also uses the same sample as “Fuck School” and some of Snoop’s inflections on “The Chronic” are very similar to the ones 3-2 used in 1990/91, particularly on “Fuck School.” In fact Death Row was so intrigued by the Convicts that they invited them to LA to record another album. But with things moving slow at Tha Row, Big Mike eventually opted for the offer to replace Willie D in the Geto Boys.

Since the slogan “Fuck School” pretty much epitomizes ignorance, 3-2 finds just the right words to diss the school system:

“Every nigga and they mama want a diploma

Then when they get the motherfucker, they still be in a coma

But 3 say to hell with school cause I don’t give a fuck

With education you can still end up workin’ on a trash truck

Teachers tryina run game and tell ya, ‘Be a scholar’

Fuck that, I’ll drop out, sell dope and make dollars

Yo, I say the same damn thing drunk or sober

Cause the best part of school is when the motherfucker’s over

[…]

It’s yo damn decision, though, don’t have a fit

Put up with the shit and in the end watch what you get

A diploma or degree for the education losers

Me need that piece of shit? Hah, when hell freezes

or when cows jump hurdles and mice eat cats

or me winnin’ pool against Minnesota Fats

bears singin’ or alligators talkin’

people without legs in wheelchairs walkin’

It just ain’t happenin, G, I can’t see it

Though you want a edumacation? So be it

You be the king of your actions, so rule

But me myself 3-2 say – Fuck school”

He insists he’s absolutely serious during “Wash Your Ass,” and Mike couldn’t be anything but sincere on the almost romantic “I Love Boning.” Unfortunately they also mean business on “Whoop Her Ass,” whose token female guest appearance by Choice can’t mask the highly questionable message. Which brings us to “Illegal Aliens,” according to the self-appointed Tribute to Ignorance (Remix) – and all around excellent blog – Unkut.com ‘to this day as without a doubt the most racist rap song ever recorded.’

From a conceptual point of view, the song does make sense within the context of the album. It voices the frustration of those who often aren’t allowed a fresh start in society, because they’re not only stigmatized as ex-convicts but also as ex-slaves. In best ignorant fashion, however, they strictly blame others for their misfortune, preferrably a defenseless scape goat. The bigotry becomes all too clear not only when they run through all the slurs and stereotypes but also when they attack immigrants in general, like the African who becomes a doctor. But the single most stupid point they make is when they decry Cubans for “runnin’ around town portrayin’ Scarface” when one of their labelmates is in the process of making a career out of portraying Scarface.

For a major part, “Convicts” is two young rappers trying to fulfil the role appointed to them by their label. Big Mike and Lord 3-2’s subsequent careers would have in fact little to do with the brashness of their collaborative debut effort. As Mike told HipHopDX in 2008: “A lot of the stuff was meant to be taken as being over the top, it wasn’t necessarily our personal views. You gotta look at it like we’re 18 year old kids. We’re trying to get on, and a lot of the song concepts were basically topics that the label wanted [us] to make a song about. That’s why when you started hearing me perform as a member of the Geto Boys, the songs concepts and the lyrics was different from what I had did on the Convicts. And you could tell throughout the years, when I started doing my solos, it was Mike, but it wasn’t the same ideas as what you heard on the Convicts. So it was really just a project that they had in motion. I just came in and did what I did without straying too far from what they was doing.”

In the end this is mainly a record for die-hard Rap-A-Lot fans who still ponder the collective production credits of these early releases (here: James Smith, John Bido, Doug King, Johny C, Simon ‘Crazy’ Collins) and savor basic but solid storytelling (a lost art in rap). There is of course a grim reality behind these tales, whether it’s domestic abuse or the conditions at Harris County Jail, but the forcedly vulgar tone (and samples from Redd Foxx, Robin Harris and Andrew Dice Clay) are liable to turn it into the comedy hour with the Convicts. Ultimately, “Convicts” embodies simultaneously everything that is right and wrong about old-style gangsta rap.