Grime is original pirate material. (No direct relation to The Streets, but there are some overlaps.) Meaning grime, born and bred in East London, live & direct, quick & dirty, has come up through that lifeline for new exciting music emerging from London Town, pirate radio. Tying into that, one thing that grime shares with the British music scene in general is that it can be a very insider thing. There is so much to know and so much to learn that it’s almost impossible to catch up once you’re late to the party. And with such an initially insular phenomenon that at the moment goes through a resurgence of international dimensions with Kanye West co-signs and editorials attesting it political purpose (Complex: ‘Is 2016 The Year Grime Becomes An Anarchist Genre?’ The Guardian: ‘Party Politics: Why Grime Defines The Sound Of Protest In 2016’), it’s very easy to be unfashionably late to grime. But even if you only possess a passing knowledge of this urban UK ting, it’s no secret that full-length releases are not a top priority in the world of grime. One of the very first ones, Dizzee Rascal’s “Boy in Da Corner,” remains its most famous album, at least on a larger scale.

Whenever someone is not that familiar with grime but still would like to offer his two cents or pence, that person is likely to come from a rap/hip-hop perspective. Which frankly isn’t the worst way to look at it. With this in mind Kano’s “Made in the Manor” has the potential to entice the critical listener who is in a position to esteem a special effort. Practicing a more mundane artform, rappers of any background have one particular artistic pièce de résistance, one touchstone to achieve, and that is the substantially ambitious album. That’s where the highest honors are. The neighborhood panorama, the life-and-times-of memoirs set to music, often offer the best shot at a personal masterpiece. Going by the titles, Kano has always been conscious of his locale on previous albums (“Home Sweet Home,” “London Town,” “140 Grime St.” – even if the latter is a fictional address whose number represents early grime’s favored BPM count). Yet “Made in the Manor” goes to the core of not so much the manor, but the man who was made in the manor.

A long way from its original historic connotation, ‘manor’ denotes simply a residential district, in rap terms the London version of a New Yorker block or hood. As chance would have it, Kano spent his early years on Newham’s Manor Road, a time and place he frequently revisits on “Made in the Manor.” He does so not only with the utmost observational precision but also the highest emotional investment. It’s seldom that you to hear a rapper convey a mood, a movement so accurately vocally and lyrically. The Kano of “Made in the Manor” is a brilliant storyteller with extra emphasis on the ‘teller’ part. His narrative presence is virtually one of a kind. Even comparisons to stateside icons like Nas or Slick Rick don’t do justice to what Kano delivers on his fifth album.

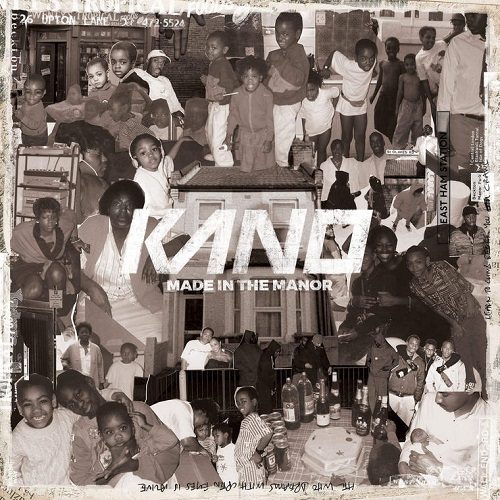

The tone is effortless with a forgiving nuance on the songs that function as recollections of places and people, of habits and rites that shaped the artist and his generation. Kano doesn’t so much analyze social conditions as human relations, all the while subtly suggesting that one often depends on the other. Throughout the album he drops a host of names, among them only a few familiar or famous ones, as if turning the pages of a photo album and saying something about this or that person in a group picture or portrait. Grime insiders will recognize certain names, but others belong strictly to his family and circle of friends. It is the mark of a storyteller that he can familiarize his audience with the subjects of his story, and while Kano remains the only constant in “Made in the Manor,” it is the presence of all these people that makes young Kano and his past come alive.

In its best moments, “Made in the Manor” transcends time – and even place – and attains universal meaning. “T-Shirt Weather in the Manor” takes us from the carefree coexistence between relatives and neighbors to suddenly changing constellations when Kano zooms in on his breakout phase when peers thought he could “take away their problems all with one hit song.” On “A Roadman’s Hymn” he shows compassion for the young men who wind up on the wrong path. “Drinking in the West End” is a lowkey look back at a night on the other side of town, an essential experience for many adolescents. The monumental “This Is England” works on so many levels at once. Dynamic musically as well as lyrically, it is proud and critical, inclusive and privy, a song that marries the personal perspective with the bigger picture:

“I’m just a Tupac nigga in a town full of Suges

Tryina be straight in this town full of crooks

Knowin’ you never seen a man buy a Bentley with a book

We take to water like a duck

Headed to the green but gettin’ caught up in the rough

Story of my life, and I’m just givin’ you the crux”

On songs like “This Is England” Kano practices socially committed rap of the highest order (“Bars back – give that dance shit a damn rest / Rap for the have-nots and the have-less”), yet he also submits his own conduct to a reality check when he contrasts his quotidian problems with real ordeals on “Deep Blues” – while still being able to put across feelings of personal despondency. Never simply the observer, Kano presents us with two particularly heart-rending songs, “Little Sis” and “Strangers.” Both are fine-grained examinations of estranged relationships and both dare to be emotional atop the analytical work Kano the writer engages in. “Little Sis,” addressing a distanced sibling, is set to a lullaby-like backdrop that invites him to lay his soul bare. All the while still succeeding to find the right words, even down to a poetically concise standalone phrase like “Family trees and olive branches.”

At one point Kano makes the argument that the people are “done with the fiction, now they want fact.” He meets that demand with a vehemently biographical album. He doesn’t forget his musical roots with a handful of more boisterous forays, notably the fearsome threesome “3 Wheel-Ups” with Wiley and Giggs. Previously released bonus tracks “Flow of the Year” and “GarageSkankFreestyle,” attached after well chosen closer “My Sound,” make for a frayed finish, but those that fit within the official sequence, including advance singles “Hail” and “New Banger,” by extension touch on the same topics as the songs that make “Made in the Manor” an auteur album. Whether single or album cut, grime or something else, the release overflows with superior lyricism:

“White chicks fling g-strings when I spit

Blacker days would’ve got lynched for this shit

Would’ve got whipped for this shit

Now I push a German whip on a bitch

Now everybody wanna get Jigga-rich quick

Want it handed to them, likkle privileged kids

Hands in the cookie jar, rippin’ off riffs

I guess that’s takin’ the flippin’ biscuit

Stealin’ a living with your sticky fingers

Crossin’ that pond and fishin’ for hits

We both gain from a little influence

But how comes nobody credits us Brits?”

Both aforementioned tunes already foreshadowed the direction of the release as Kano reflects on his environment in vivid detail. They are a natural fit for the album while “Seashells in the East” returns to the “t-shirt weather” theme, continuing the truly rare lyrical performance with loads of thoughtful lines, another way with which Kano brings his magnus opus full circle.

“They say grime’s not poppin’ like it was back then / Rap’s not honest like it was back then,” he reasons in the first song. With the subsequent efforts Kano does his best to remedy the situation. He rises to the ultimate album crafting challenge in a way that wasn’t foreseeable. If the world won’t completely turn upside down, “Made in the Manor” will go down as one of the classics created by British MC’s.