“Redhead Kingpin, Tim Dog, have you seen ’em?

Kwamé, King Tee, or King Sun

Superlover Cee, Casanova Rud

Antoinette, Rob Base, never showin’ up

You seen Black Sheep, Group Home, Busy Bee?

Ask Ill & Al Skratch where my homiez

Leave it to y’all, these niggas left for dead

Last week my man swore he saw Special Ed

Rap is like a ghost town, real mystic

Like these folks never existed

They the reason that rap became addictive

Play they CD or wax and get lifted”

(Nas, “Where Are They Now?” 2006)

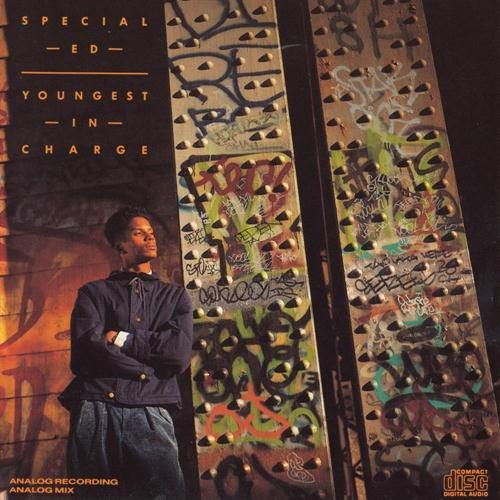

Last time I swore I saw Special Ed was while watching a re-run of _The Cosby Show_, where, as the credits confirmed, in a 1991 episode he plays rap star J.T. Freeze. First time I heard him was in 1989 with “The Magnificent,” an infectious reggae-tinged tune propelled by a playful guitar loop extracted from Desmond Dekker’s rocksteady classic “007 (Shanty Town)” that announced its arrival with a vocal sample from Dave & Ansel Collins’ “Double Barrel.” Back then “The Magnificent” was the highlight of a radio show I had taped, and enough reason to seek out the album it was on. Presently, I can choose from CD or wax to get lifted from “Youngest in Charge,” while potential buyers now might have to invest a bit to obtain an original copy.

“The Magnificent” was an energy booster for inert masses as well as a tasty lyrical treat that served as an introduction to the witty verbiage of Special Ed:

“I’m the magnificent with the sensational style

And I can go on and on for like a mile

a minute, cause I get in it like a car and drive

And if the record is a smash I can still survive

Cause I’m the man of steel on the wheel that you’re steerin’

or rather playin’ on the record that you’re hearin’

You might not understand what I’m sayin’ at first

So Akshun Luv, put it in reverse

( *backspin* )

I’m just conversin’ with your person, this is just a conversation

I’m Special Ed with a special presentation

Hey, I like to play, so for me it’s recreation

It’s not just a job, it’s an adventure

If worse comes to worst I’ve got the thirst quencher

But you gotta buy it, don’t even try it

I don’t rhyme for free, no matter how dry it

gets; I collect my money in sets

One before the show and again when I jet

So I get mine and I’ma get more

Cause I’m financially secure and I’m sure

So I don’t need your tips or advice

Cause I’m too nice for that, you rat, I can’t stand mice

I’m like a cat, kind of frisky, battlin’ is risky

business; you might acquire dizziness just like whiskey

Isn’t this enough? Oh, you think you’re tough

cookie, I think you better call your bookie

cause you can bet your life that I’ma play ya like hookey

on a Friday, this is my day

When I was through I heard you say: ‘Why they

diss me like that? I should’ve repent

Somebody should’ve said that Special Ed was the Magnificent'”

Being cocksure seemed to come natural to Edward Archer. Off the record, however, he was your average New Yorker teenager. It was when his voice was amplified that he became The Magnificent. Still a minor while writing “Youngest in Charge,” he did not forget to shout out his high school, Erasmus Hall in Brooklyn’s Flatbush section, once he got a chance to cut a record. In retrospect, he had every reason to assume a confident mic persona, as his debut single became one of those ’80s songs that would define hip-hop for generations to come. “I Got it Made” is not just a blueprint for rap songs that chronicle wished-for success, it’s also a testament to how keenly aware rappers are of the power of words. “I Got it Made” is first and foremost a rap about rap, self-referential, self-centered, and just outright fun to listen to. Starting with the immortal opening line “I’m your idol, the highest title, numero uno,” Ed continues with various claims pertaining to this gift of gab. He is keen to point out that the everyday language he uses doesn’t take anything away from his rhetorical skills: “I’m outspoken, my language is broken into a slang / but it’s just the dialect that I select when I hang.” And in one of rap music’s most significant moments, he displays wisdom beyond his sixteen or so years:

“I talk sense condensed into the form of a poem

Full of knowledge from my toes to the top of my dome

I’m kind of young, but my tongue speaks maturity

I’m not a child, I don’t need nothin’ for security

I get paid when my record is played

To put it short – I got it made”

To put it short, he had it made. Yet unaffected by whatever lessons the music business had in store for him, to young Edward there was no doubt that he got paid when his record got played. Rap music has since seen innumerable songs that claim their authors are paid. Over the years, more spectacular sources of income have replaced selling records, preferrably illegal ones. Not so for Special Ed, who by his own account had a real record to attend to, not a criminal one to refer to:

“I’m talented, yes, I’m gifted

Never boosted, never shoplifted

I got the cash, but money ain’t nothin’

Make a million dollars every record that I cut, and

My name is Special Ed and I’m a super duper star

Every other month I get a brand new car

Got twenty, that’s plenty and I still want more

Kind of fond of Honda scooters, got seventy-four

I got the riches to fulfill my needs

Got land in the sand of the West Indies

Even got a little island of my very own

I got a frog, a dog with the solid gold bone

An accountant to account the amount I spend

Got a treaty with Thaiti cause I own a percent

Got gear I wear for every day

Boutiques from France to the USA

And I make all the money from the rhymes I invent

So it really doesn’t matter how much I spend

Because yo, I make fresh rhymes daily

You? Burn me? Really?

Think, just blink, and I made a million rhymes

Just imagine if you blinked a million times

Damn, I’d be paid

I got it made”

If “I Got it Made” dropped today, to most people it would probably be more of the same. But it’s not. Modest in its musical means, this is low-budget hip-hop in the best sense of the word, simple yet effective, limited yet ambitious. Catchy, creative, clever. The video clip for the song was disarmingly basic, its unpretentious approach best illustrated by Ed walking around a scrapyard passing piles of car wrecks while rapping about his car-buying habit. To Ed, his dreamt-up fortune was merely a metaphor for his rapping ability. In fact, he took the concept of the wealthy rap star to absurd heights, interspersing the most outlandish claims with casual tasks, and injecting it all with a healthy dose of humor:

“I’m kinda spoiled cause everything I want I got made

I wanted gear, got everything from cotton to suede

I wanted leg, I didn’t beg, I just got laid

My hair was growin’ too long, so I got me a fade

And when my dishes got dirty, I got Cascade

And when the weather was hot, I got a spot in the shade

I’m wise because I rise to the top of my grade

Wanted peace on Earth, so to God I prayed

Some kids across town thought I was afraid

They couldn’t harm me, I got the army brigade

I’m not a traitor; if what you got is greater I’ll trade

but maybe later cause my waiter made potatoed alligator soufflé

I got it made”

On “Youngest in Charge,” “I Got it Made” is preceded by “Taxing,” which takes the musical-talent-equals-money metaphor one step further as all this happens at the expense of the rappers he, erm, taxes. “Taxing” is also one of the earliest rap songs to describe audience and rapper getting high, mentioning blunts and forties, “cause stimulation is what helps my creations / you know I get mellow before my presentation / because it helps my rhymes to flow through / like water; I caught a brew, on second thought a few / to release all the heat that I kept / when I was sober, so now it’s overstepped.”

Another noteworthy feature of “Youngest in Charge” is the violence it contains. Which is, although graphic, again strictly metaphorical. Figuratively, he does competition something terrible. Going up against Special Ed, rappers are in mortal danger: “If you try to riff you’ll be stiff on the way back home inside a box.” In fact, his main incentive for rhyming seems to be murdering MC’s: “Sometime I wanna rhyme but then again I must wait / for the approaching of a toy to introduce him to his fate: / Death; I always try to figure out why / sucker MC’s wanna battle me when they know they will die.” He’s a cowboy, roping them up. He stifles them with microphone chords. He makes them bleed until they need a transfusion. He burns them as he turns them like a shishkebab. He runs them over like a truck and leaves them dead in the street. He has them running for their lives like they’re swimming away from Jaws. He likes shoot-outs. And if preferred, he gets the steel-toe boot out. He gives tumors. As well as eye-jammies. He slams them and kicks them. He bites their faces just to taste them and lick them. And then hands them over to his DJ to finish them off:

“Akshun Luv is cuttin’, I’m on the rhyme

Skin your teeth, then it’s your beef that I grind

Like a butcher I put ya on the table

and let my DJ cut ya, but you’re such a little sucker

I might not even touch ya

I bet ya what ya want is just attention

Your mother and your father should’ve used some prevention

Look at all the time and the money they spent

And now you wanna die against I the Magnificent?”

To add insult to injury, he resurrects his victims into an even worse afterlife:

“Stop your heart, take your breath

with the diagnose of death

Remove your brain from your skull

make ya dumb, make ya dull

Sow you up and cut your hair

Put you in a science fair

Tell ’em that your name is John

make you a phenomenon

Freak of nature, make ’em hate ya

Not a girl will ever date ya”

Special Ed was aware of his penchant for violent imagery. “Club Scene,” a duet with female rapper Kazaam, who ponders that a rap, or more specifically a rap battle “is supposed to be pleasant / not the annihilation of a peasant,” is his chance to show a more peaceful side. At her request he agrees, “I’ma chill,” but can’t help himself and follows the promise “But I can and will get ill” up promptly: “I’ma break some jaws and bones / forget sticks and stones.”

The beautiful thing is, Special Ed doesn’t actually sound like he is capable of administering all that pain. And he knows it. He’s a writer, not a fighter. But in a war of words he’s intent to have the upper hand. Ed’s special skill was to fly heads with the intuitive nonchalance of a black-belted martial artist. He wasn’t screaming at you, rather he enhanced his mellow, melodical vocal tone with a clear diction and crisp delivery, the intonation, if need be, revealing the irony in his lyrics. The patterns, often equipped with internal rhymes, were simple, broken up by sentences who ended just beyond the next rhyme, word association giving his lyrics an arbitrary as well as logical appeal. “Youngest in Charge” felt like you just stepped into a freestyle session, the special thing being that this guy, though casual as anything, was definitely prepared. Not just lyrically, but also mentally. Add to that a natural flair that you just can’t fake and you end up with that strong feeling of superiority that just needs a couple of tongue-in-cheek two-liners to express itself fully: “My rap is like a trap that you fall into / I’m Special Ed, now who the hell are you?” One of the most memorable displays of such snobbery is “Fly M.C.,” an astounding account that ends with Ed kicking the queen of France off a plane in mid-flight. You gotta hear it to believe it. The second storytelling effort is the hilarious “Hoedown,” a rap-meets-bluegrass (or, as the sampled Wilbur Bascomb would have it, “Black Grass”) mash-up to accompany the Slick-Rick-esque freaky tale.

Besides his high school and his stomping ground, the Brooklynite is shy about revealing vital stats. The hints at who Special Ed really is when he’s not The Magnificent, are few and far between. The closing “Heds and Dreds,” where he toasts over a reggae riddim, alludes to his Jamaican heritage. He also dedicates a track to his trusty pal Akshun Luv (“You’ll say: ‘I want a DJ just like that one!'”). “The Bush,” which engineers Al Green’s “Love and Happiness” into an urban jungle groove James Brown would be proud of, acts as a warning to outsiders, and could also serve to explain the violent code of Special Ed’s battle rhymes:

“If you come to the Bush, keep a low pro

cause you might catch a knot, or a shot, or a blow

to the face in this place; if you base, you will be broken

Comin’ off the train you gotta pay another token

What this means is you pay for your protection

Pay a fee and never see a reflection

again my friend, or rather foe, you know the deal

Either hear or feel

Choose one, but at least you got an option

Be my son or be up for adoption”

“Youngest in Charge” is another specimen that breathes hip-hop history, right down to the commercial “Club Scene,” which ambitiously keeps reinventing itself but still marks the album’s low point. Like our man says, “If you’re lookin’ for a Brooklyn jam / here’s one you might like about a mic and a man.” This is what “Youngest in Charge” is all about. Brooklyn’s own Special Ed, as seen through his charming self-aggrandizement. There is something intriguingly quick and dirty about a record whose first two tracks sample from the same funk band (Ripple) and whose third track samples two songs that happen to be on the same soundtrack (“Harder They Come”). Produced at Howie’s Crib in Flatbush by the oft-forgotten Hitman Howie Tee, it is an effortless piece of work, marrying colorful, sample-based, yet simultaneously stripped-down compositions (with percussion in an essential supporting role) and the agreeable rulership of the self-acclaimed Lord of the Rhyme.

Remembering the video to “Think About It,” where Ed raps from a hovercraft chased across an outdoor scenery, there’s no doubt that to Ed this rap stuff was indeed an adventure. Staged in hip-hop heartland, starring a high school student, “Youngest in Charge” doesn’t possess the intimidating presence of its more prominent peers. But as an example of rap’s originality (one of those things money can’t buy), it still stands tall, in some aspects technically inferior, but definitely “creatively superior.”