“Lyrics are fabrics, beat is the lining

My passion for rhyming is fashion designing”

(Kool G Rap, “Poison”, 1989)

There should not be a shred of doubt in anyone’s mind that fashion and rap music and hip-hop culture are almost inseparable. The commercial exploitation of the relationship began with Run-D.M.C.’s Adidas deal, but appearances already mattered before Jason, Joseph and Darryl heralded hip-hop’s new school both musically and stylistically, like when the Cold Crush stunned concert goers and competition when they dressed as prohibition era gangsters, prop Tommy guns included. Rappers have only gotten more serious about their outfits since then, a considerable number having gotten involved in fashion designing (in what actual capacity is another question).

You can evoke specific seasons in rap music just by tossing in brands, accessories or fabrics: Kangol, kufi hats, bandanas, shiny suits, missing shoelaces, durags, dungarees, Tommy Hilfiger, Avirex, baggy pants, skinny jeans, Raiders jackets, Northface, Nautica, Cazal, double gooses, rolled up pant legs, Lugz, ski masks, ski goggles, Bally, beanies, parachute pants, Gucci, Coogi, DKNY, pimp attire, leather medallions, camouflage, Chuck Taylor, Helly Hansen, Timberland… The rap business has been good to stylists.

It’s hardly surprising then that rappers discuss wardrobe in their lyrics. The discursive nature of rap brings forth opposing opinions. Up-and-coming underground vanguard Eto said for instance in 2019: “Listen to old Ye, but I don’t wear Yeezys” (“Strip Talk”). In both the world of rap and fashion it’s all about finding your own position. Nobody would ask Eto to defend his because to be honest there was something off about Kanye West and fashion ever since he claimed on Rhymefest’s “Brand New”, “Ralph Lauren was borin’ before I wore him”. Which, in the context of rap, is as absurd a thing as you can say. But if that would have remained the most absurd fashion statement made by this individual, we could consider ourselves lucky.

There’s a lot to criticize about the relationship between the rap industry and the fashion industry in general. How hip-hop celebrities seemingly stopped championing homegrown (although not uniformly black-owned) brands like Cross Colours, Karl Kani, Pelle Pelle, FUBU, Phat Farm, Wu-Wear, Sean John, Mecca, Enyce or Rocawear and turned into billboards and mouthpieces for global luxury brands. How in the ’90s some traditional American companies snubbed their newfound urban customers. How hip-hop artists went from rocking something with style to thinking a name logo gives them style. How hip-hop and high-end fashion are ultimately hard to reconcile, as much as those who profit try to ignore the fact. And while we’re at it, how so-called streetwear has claimed plenty of fashion victims over the years.

Another persistent issue is the money spent on clothing. Name-brand clothes have never been cheap, still expensive streetwear is sort of an oxymoron, and when companies bait customers with exclusivity, it’s just the old status symbol game. Selling dreams is an old trade, but overpricing corrupts the authenticity that streetwear represents in the context of fashion.

It always begins innocently enough, with creativity and enthusiasm. Fashionistas should be familiar with the name Hiroshi Fujiwara, a Tokyo trailblazer whose sense for styles and trends enabled him to become an intermediator of US and UK youth cultures, beginning with the punk movement, then making a crucial stop at hip-hop on his way to becoming an icon of Japanese club and street culture. With fellow DJ Kan Takagi, Hiroshi Fujiwara formed the group Tinnie Punx (also spelled Tiny Panx and in other variations), who, in collaboration with Seiko Ito, released the first Japanese record to include notable amounts of rap vocals, hip-hop rhythms and turntable work in 1986.

Their musical experimentation evolved into Major Force, a hip-hop/dance imprint that put out some of the first serious interpretations of hip-hop music in Japan. With its distinct design, the Major Force brand was an incubator for early Japanese streetwear as well.

Fujiwara and Takagi also conceived a column in 1987 that furthered their reputation as tastemakers. One of their followers, Tomoaki Nagao, felt inspired to move to Tokyo and take on fashion journalism. He met Fujiwara and eventually became his assistant. Due to their likeliness and shared vision, Nagao was nicknamed Fujiwara Hiroshi Nigo, the latter term translating to ‘number two’.

Nigo took being called Hiroshi Fujiwara II to heart. Together with former classmate Jun Takahashi he resumed the style column originated by Tiny Panx and in 1993 opened the store NOWHERE in Ura-Harajuku, Shibuya’s microcosm of backstreet boutiques, which carried their respective clothing brands A Bathing Ape and Undercover. All that was missing was the musical venture.

Next to being tagged for singer/rapper Yuri’s styling back when the group East End x Yuri briefly said hello to the world on behalf of Japanese pop rap, Nigo’s name appears in 1997 in conjunction with British electronic music project UNKLE, whose founder, James Lavelle, had long been an advocate of Major Force outside of Japan, making their output available through his Mo’ Wax label. A breakbeat-style collage featuring dialogue from the ‘Planet of the Apes’ franchise, “Ape Shall Never Kill Ape” was co-produced by Lavelle and temporary UNKLE member KUDO, himself an integral part of Major Force, with slicing cuts added by the UK’s Scratch Perverts. Nigo makes the track’s marquee because it’s obviously a not-so-obvious Bathing Ape plug.

Another cross-promotional endveavor was the 1997 mix “A Bathing Ape vs Mo’ Wax” compiled by Nigo and Lavelle. The commercial intentions are always elegantly tucked beneath the creative ones in these circles, still here we find music, design and fashion converging to target a relatively exclusive circle of customers. Nigo the recording artist then fully emerged with 1999’s “Ape Sounds” LP, which he produced together with KUDO.

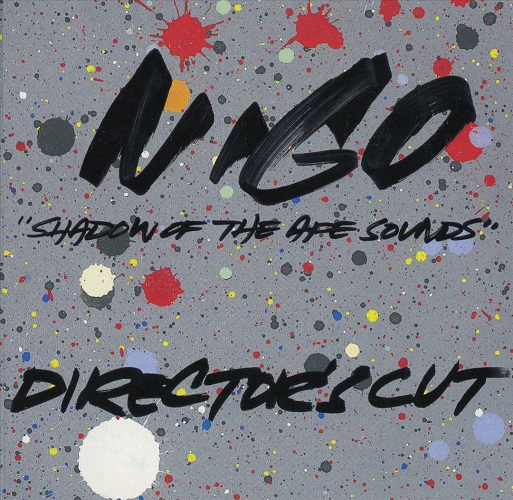

The UK connection was maintained with distribution by Mo’ Wax and a remix version of the album. The project at hand, “Shadow of the Ape Sounds”, however, flipped the script entirely. While “Ape Sounds” was a melange of big beat, pop, alternative rock and hip-hop with a single rap performance by Major Force godfather Tycoon Tosh, “Shadow of the Ape Sounds”, released in 2000, went for the big-name US features.

A series of singles, followed by remixes for each track, finally gathered in full-length form as “Shadow of the Ape Sounds – Director’s Cut” – the release history catered to record buyers and collectors, comparable to how some fashion brands market their clothing or sneaker lines. In keeping with the theme of exclusivity, the guest list was limited and only featured Golden Age representatives or acts who already had taken their place in the pantheon of East Coast hip-hop. (Although, as far as exclusives go, DJ Honda had Biz Markie and The Beatnuts already on his ’95 record.)

Nigo’s scoop was a cameo from Rakim, who, considering his stature, has made few guest appearances throughout his career. That is not the only reason “Once Upon a Rhyme in Japan” is a remarkable international collaboration. Rakim paints himself as “rap’s ambassador” who looks benevolently upon the Japanese hip-hop congregation, giving props and delivering words of encouragement. The opening verse is a carefully set up testimony to how solid Japan’s hip-hop practitioners are:

“Once upon a rhyme, but way across the maps and seas

In a time that’s hard, all we have is dreams

In a place surrounded by casualties

B-boys and girls wear caps and jeans

They have to fiend, infected by rap’s disease

But prepared to die for all of rap’s beliefs

They love real hip-hop, real tracks and MC’s

And can’t stand cats that like to rap for cheese

It ain’t all about the gat that squeeze

VS-1’s or SUV’s or even stacks of g’s

They love thuggin’, but still they like to catch a breeze

They love clubbin’, so they go and crash the scene

Where the queens treat they men like kings, your majesties

DJ’s trickery spins the wax with ease

On the dancefloor spinnin’ on they backs and freeze

Where MC’s kick rhymes in Japanese”

It’s a whole different level of sweet-talking a local audience. The beat for “Once Upon a Rhyme in Japan” marries heavyset, sluggish drums with poised sitar strokes (that evolve into a veritable solo after the 5-minute mark) to create a distinctly foreign panorama as far as an US MC’s experience goes.

The trio of KUDO, Nigo and Kan Takagi put together a dense, precisely crafted record. “From New York to Tokyo” builds like some psychedelic world music before seguing into a rhythm section of bass bubbles and stuttering snares. Over this spellbinding stew we find Public Enemy jokester Flavor Flav making a rare solo appearance. A one-of-a-kind hypeman as much as an underused master of ceremony, he gives anything but an impromptu performance, as a bit that sounds like a foreign language course for preschoolers makes more sense than you would imagine and the fact that he namedrops many of the project’s collaborators indicates how much Nigo wanted “Shadow of the Ape Sounds” to be perceived as a whole. The totally far-out ’90s Flavor Flav solo album never materialized, but for it to work, it should have possessed that kind of adventurous spirit.

“Something For the People” with Biz Markie wouldn’t have been out of place on the Gorillaz debut with its chugging indie pop/rock vibe. (In contrast, DJ Krush’s remix is lean and sparse and mindfully samples from “Make the Music With Your Mouth, Biz”.) Meanwhile the premise of “Very Good My Friends” sounds more fun than the track actually turns out, considering we’re dealing with the world’s famous Beatnuts. At least tag-along E-Swinga gets a FUBU reference in.

Measuring up to expectations, “K.F.F.2000” lays out a droning soundscape for GZA and Prodigal Sunn (who both also guested on a German tune together in 2000) to apply their artistic senses steeled by the consumption of Hong Kong movies. As always, GZA is able to use the imagery at hand:

“I see gorillas in the mist with Bathing Apes

Banana clip carriers of hip-hop tapes

Record in the Milkcrate, Athletic MC’s

Do laps around the track, still sting like the bees

While the geisha work the tea house I’m in a tree house

She walk around the trap I set like a free mouse

My Wu-Tang logo on the back of her kimono

Beat play in the background on the phono

My kung-fu be the Tung-Wu

Look for the dragons when they come through

On the manual the titles embossed in caligraphy

I swing a sword, heads rollin’, respectfully”

RapReviews.com recently retraced recorded appearances of American rap artists in Japan in the period between 1985-2007. In that context, the features that Nigo managed to nab are simply a few among many. Quite a few of them based on deep mutual understanding that went well beyond the commonality achieved here. Still the project as a whole is noteworthy because there’s a vision behind it while many international rap features are more or less accidental. Meanwhile the Ape Sounds team made sure to commission domestic remixes by DJ Krush, Yann Tomita, Muro, Shinco, Force of Nature and the late Dev Large (who urges the Beatnuts track in a bluesy direction).

Nigo continued his musical career for a couple of more years (including a stint as label boss/sponsor/DJ for fun supergroup Teriyaki Boyz) before concentrating on fashion, a lane that in 2021 took him to the position of artistic director for Parisian luxury fashion house KENZO (founded in 1970 by countryman Kenzo Takada). On his own records, he acted probably more as a consultant or curator, given KUDO’s vast experience (and Nigo’s relative inexperience).

Nigo’s legacy in regards to hip-hop remains attached to A Bathing Ape, a brand that simultaneously continued the ’80s/’90s innovation of what was dubbed remix culture and conducted business in a way that mostly only privileged customers were able to acquire its products. In fact, Bape’s full initial name – A Bathing Ape in Lukewarm Water – was an tongue-in-cheek dig at a certain set of spoiled, complacent kids – who would soon be among the brand’s first backers. These contradictions converge if you acknowledge that the successful Bape Sta sneaker imitated Nike’s Air Force 1 and also can’t forget about ’07 teen rap sensation Soulja Boy, who was, by any indication, bragging about having bought fake Bape (Fape) items in his early hit “Bapes” (aka “I Got Me Some Bapes”). Bless Rakim for trying in “Once Upon a Rhyme in Japan” but real, fake – can you really ever tell with hip-hop at all?

Yet the allure is undeniably there, regardless of authenticity. Image is not everything, but it’s such a big part of what makes street culture attractive to enthusiasts and investors. If you follow hip-hop and the industry it continues to feed, you know that it continues to speak the code of cool. More importantly, being – and feeling – fly or fresh is not just a superficial attribute in hip-hop. Observers also point out that the aesthetics and branding of A Bathing Ape (or any label that associates itself with the youth and the street) are (or were) vital to an adolescent, urban Japanese lifestyle that included elements of hip-hop. Which is a lifestyle not solely defined by consumerism because it still can be seen as a counterculture within the context of Japan. We may have gone from hip-hop culture to hip-hop couture, but the vitality is somehow still there in all of it.

Today Nigo is usually introduced as a friend and business partner of Pharrell Williams. They go back to the Neptunes days, and Pharrell was a sure bet for Nigo’s 2022 comeback album “I Know NIGO”, which squarely relies on modern vibes (the guest list including Pusha T, Kid Cudi, Pop Smoke, A$AP Rocky, Tyler, The Creator and Lil Uzi Vert). If you happen to come across it, its predecessor in regards to Nigo’s US rap connections, “Shadow of the Ape Sounds”, is a worthy trip back to a different era in hip-hop off the beaten path nostalgia usually takes us.