As the Wu-Tang Clan prepares to launch their (supposed) final album, it’s worth reflecting on the global impact they have had on music, particularly Hip-Hop. The extended family tree of affiliated artists has more branches than Nick Cannon’s Ancestry account, and by the time you get to the late 2000s, the return on investment was certainly dwindling. An artist who sticks out as an extreme example of this is Brooklyn’s Lone Ninja, who was able to craft incredibly creative raps, albeit lacking the required charisma to match the wisdom. There are many underground rappers that navigated this arena of fantastical character-rap which combined science fiction with historical references, often sacrificing flow and delivery in favour of saying some cool shit. This style can excel when delivered by an emcee who can show flexibility with their delivery: a personal favourite of mine is London’s Cyrus Malachi because he’s doing this with an imposing, punctuated presence that is impossible to ignore. The way you can hear him suck in air before unloading a bunch of punches armed with years of learning isn’t dissimilar to core Wu mainstays like Cappadonna or Killah Priest. Philly’s Chief Kamachi is another example, and his latest project “GODBODY” highlights more than ever that the underground rapper operating in this lane remains fascinated with spirituality – specifically the history of African gods, Egyptology and the portrayal of Black men as gods, and Black women as goddesses.

While a lot can be learnt from listening to Hip Hop that references African history and African mythology, more often than not, it’s being delivered by an American with African ancestry. In the case of Johannesburg’s Yugen Blakrok (originally from the aptly named Queenstown), listeners get to hear grimy, mystical raps from an African, which may sound like a bizarre thing to point out, but Afrofuturism is the banner that Blakrok operates under, and it’s largely accurate. The Western world is so rarely treated to African artists operating in this subcategory of atmospheric, wisdom-rap, so listening to Yugen Blakrok is a bit of a treat. Especially as she only releases albums every six years. “The Illusion of Being” is the closest example of a soundtrack fitting this wanderer aesthetic, and knowing that much of it was written in the mountains of Catalonia (Spain) in near-complete solitude, it also feels more authentically created than someone name-dropping historical references they read on the Internet.

Another reason why I cite obscure Wu-Tang offshoots that felt too underground to the point where it could be a challenging listen is because that’s what Yugen Blakrok’s 2013 project “Return of the Astro-Goth” feels like retrospectively, particularly after listening to her latest album “The Illusion of Being”. A decade of growth is evident, yet her style remains as unorthodox and unpredictable as it did before. The writing often dribbles over into the next bar of the beat, noticeable when she’s rapping alongside the personality of Sa-roc on “The Grand Geode”, one of the album’s highlights. An easy way to describe Blakrok’s style is as a calmer, more calculated Sa-roc.

Their styles are so similar that I thought Sa-roc was up first, but Sa-roc does that Akinyele-like vocal inflection to help distinguish her rhymes while simultaneously elevating Blakrok, who could easily have been shoved aside by, let’s be honest, one of Hip-Hop’s most vicious emcees. I could see the two working well together again.

Those familiar with Blakrok’s world-building, which was fostered on 2019’s “Anima Mysterium”, won’t be surprised by her ability to guide listeners through some dark, sometimes bleak soundscapes. Production is mostly from longtime collaborator Kanif the Jhatmaster, and he excels in the album format, but there are a few additional names that reflect the global travels Blakrok has experienced in the last few years (she’s now based in Marseille, France). British producer Lee Scott laces “The Shining”, Germany’s Werd Pace delivers “Loner”, and presumably British Mark Andrew Sunners gives us “Fighter Mantra”. Individually, I would say that a lot of these beats don’t really stand out with memorable melodies or samples for your ear to latch on to, but as one cohesive hour (well, 51 minutes) of immersive Hip-Hop, it definitely succeeds. This is headphone music, where you’ll want to absorb each bar:

Being Here (verse 2)

“I love blunts love grunge love stirring up dust

Hot-tempered temperamental might come across rough

A bit like diamond uncut ask any shadow i’ve crushed

I’ve suffocated spaces breathing matter into my lungs

Body temple coffee-coloured skin-covered relic doors

Woolly hair in kinky coils catching codes kemetic law

Morphogenetic or 3D pineal-like prosthetic horn

Black Lorde like Audre versed in poetic lore

I see sound in wave forms and red tones scorch me

Found a spot underground and crawled in, crawled deep

Blues girl like anime, the music’s in my force field

Society malfunctioning the wiring is faulty

Surely, not by hazard if you’re heeding the signs

Don’t believe in the hype and keep your frequencies high

In-fighting just distraction from the truth they’ve been hiding

Our brothers and sisters silenced to keep us weak and divided”

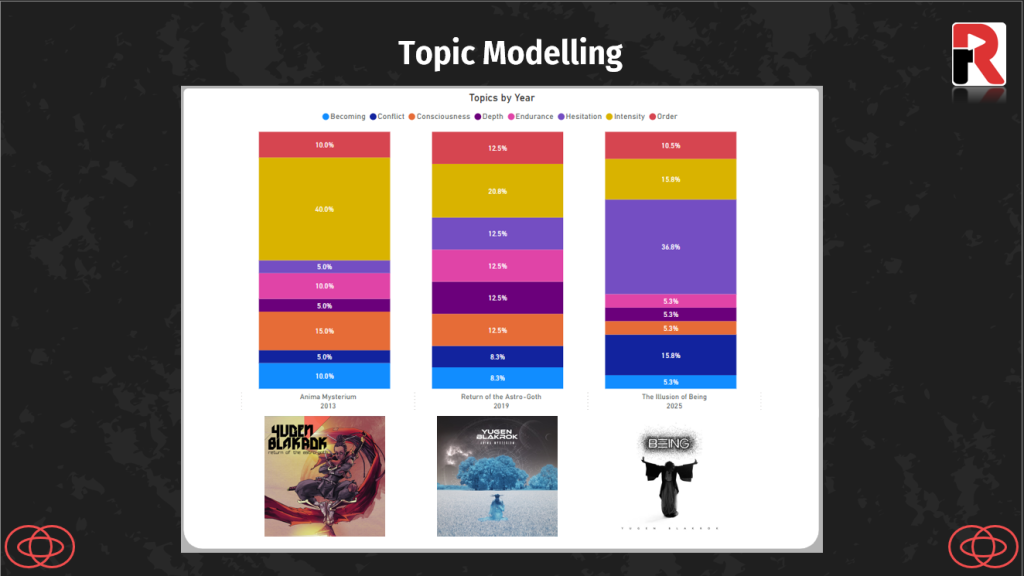

What’s evident from listening to Blakrok’s three albums is that she’s doing more with less. “The Illusion of Being” is understandably contemplative, judging by the title alone, but is backed up by doing some analysis on her verses. Themes like Hestitation (words such as “could,” “don’t,” “till,” “nothing”) and Conflict (“fighting,” “wars,” “fire,” “lost”) dominate, whereas previously in her career, verses were geared more around Intensity (“dark,” “mental,” “wild,” “smoke”) and Consciousness (“within,” “mind,” “thoughts,” “focus”, “rising”, “shining”, “silver”, “clouds”). This makes a lot of sense considering the album promo has highlighted these are “songs for those waging silent wars within themselves”,

Blakrok states in a recent interview that “My relationship with South Africa has changed. I’m less angry now” and this is evident in her shift away from utilising more intense language.

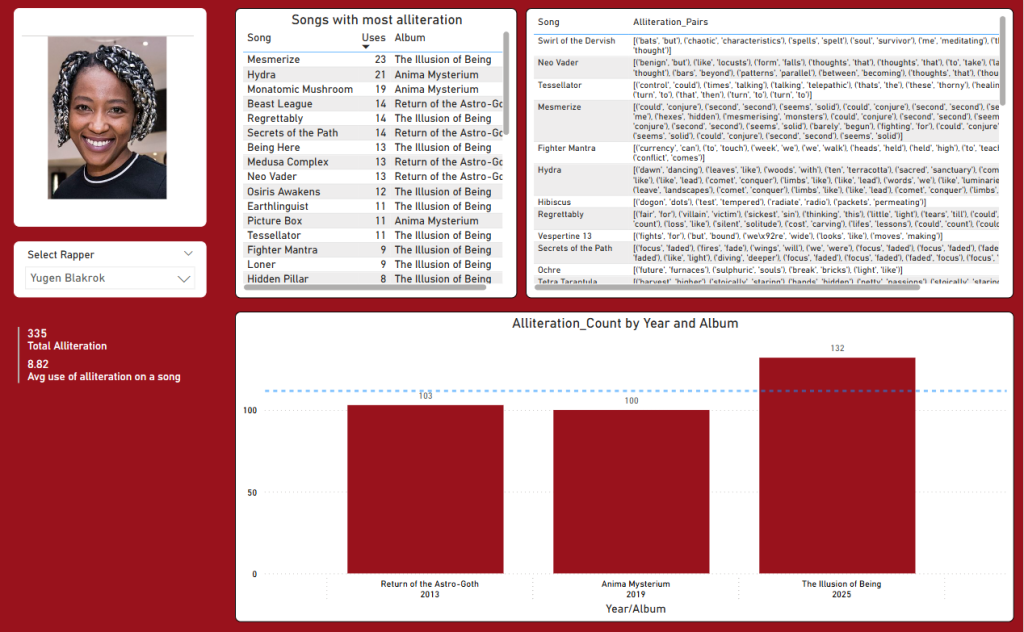

Collaborations with the aforementioned Sa-roc, as well as the scathing force of nature that is Cambatta (on “Tesselator”), feel more intentional than the more immediately abstract use of Kool Keith on 2019’s “Mars Attacks”, but also feel like a step up in terms of pure lyricism. Speaking of lyrics, the turntable scratches of “Mesmerize” and “Tesselator” don’t just remind you that you’re listening to a rap record, but they are essential to help break up what is Blakrok’s wordiest set of songs since her debut. “Mesmerize” also sees Blakrok using alliteration the most in her career (23 times).

Alliteration is up on average from eight uses per song on the last two albums to ten uses per song, highlighting how her time in the mountains writing this record has pushed her pen to the next level (for context, Nas’ average is twelve per song, and Chino XL’s is fourteen). Profanity has always been minimal in the South African’s arsenal, and has dropped off the Cliff of Bandiagara, from 6 to 3 to just the one use of “shit”.

Blakrok’s style of scene-setting and hiding jewels in her verses feels better than it’s ever been, but it’s the more effective production that elevates this album from the crowded underground scene. “Hidden Pillar” sounds like you’re stomping across sand dunes in the Sahara, potentially stumbling across some Stargate-like portal to another realm.

It should be stated that this isn’t an album for everyone, and I’m aware that an emcee like Sa-roc has a divisive vocal presence, so the same applies for Yugen Blakrok, whose heavier reliance on spitting spirituality ensures she’ll either be something you appreciate, it’ll go over your head, or you may just not want to hear this type of rap. I really like this album, but songs like the more experimental and disruptive “Grand Rising” felt a bit too chaotic for an emcee who’s all about delivering thoughtful screenplays. It’s in the heavy bass and plodding drums that I find this album succeeds the most musically; “Osiris Awakens” with Mohama Saz is a great example of this and allows Blakrok to breathe, as her wise words have time to be processed.

If you check Yugen Blakrok’s Wikipedia page, it unfairly boils down her notability to one song (“Opps” with Vince Staples), which was featured on the Black Panther original soundtrack. It put her on the map for many, particularly if you’re not up on the South African Hip Hop scene (which I am not), but it makes sense for Yugen Blakrok to move away from Africa to continue her career. Hollywood may have come and gone, but much of the world remains fascinated with African art and African music. It’s not going to do the numbers that her compatriot Tyla is currently doing, but this isn’t music to mindlessly shake your rump to. This is more like reading a book, or watching a film. “The Illusion of Being” is what a lot of American (and European) rappers think they are making, and Yugen Blakrok has done what many underground artists aren’t doing – she’s grown, she’s improved, and she’s the best she’s ever been.