Although he had already rapped about the now epic ‘EastEnders’ soap opera as early as 1987 (in a typically gimmicky mid-’80s rap tune that went absolutely nowhere), the British audience took proper notice of Michael West when he was emceeing dancey, acid house-inspired tunes by production team Double Trouble in 1989. His appearances on the singles “Just Keep Rockin'” and “Street Tuff,” who both charted, served as warning examples for the supporting role British rappers had no desire to be relegated to. Both songs were recycled for his 1990 debut “Rebel Music,” which couldn’t dispel the impression that Rebel MC was a lightweight able to fulfill the rap needs of the pop/dance world, but not those of the hip-hop movement.

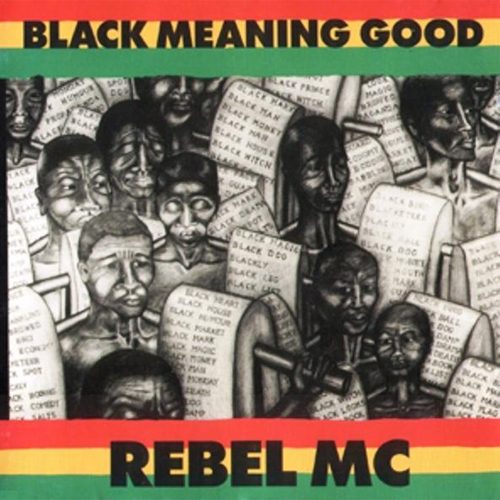

One year later Rebel MC took everyone by surprise with the release of “Black Meaning Good.” Cleverly paraphrasing the classic Run-D.M.C. bon-mot “Not bad meaning bad but bad meaning good,” Rebel MC had nothing less than a linguistic reform in mind when he attacked the fact that in English (and not only there) black is often synonymous with bad:

“Definition of black is the opposite to white, right?

On the mic to set the wrong right

The prefix of ‘black’ to a word means bad

Black sheep, black magic, kinda tragic, uhm, sad

Black is sinister, peace in the light

Conditioned negativity, stereotyped

White is pure, pure is white

Many they are sufferin’ from short sight

Check the story of the past, pure lies

And race hate, you see it in their eyes

Conditioned to thinkin’ that bad is black

In case you don’t know, that’s (wick-wick-wick-wack)

So don’t check this as a racial reaction

It’s just a study of black exploitation

Watch TV and see another black pimp

To one who don’t know, what do they think?

Black man, black pimp, then make a link

Black sheep, black lie – more words of the negative

What does it mean? Blacks aren’t positive?

Martin Luther, Malcolm X and Marcus Garvey

Moses and rasta Marley

E.G. the theory is wrong

For those who don’t know, I put it in a rap song”

“Black Meaning Good,” the combative album opener, doesn’t probe the etymology of terms like black market or black plague and therefore jumps to conclusions linguists would likely reject, but it still reveals a fundamental pattern in our society that ‘people of color’ (as the Americans say) are subject to. A pattern which rap, more than most other genres of entertainment, is fit to address. Even if Rebel MC could be accused of jumping on the political rap bandwagon, he still made a noteworthy statement none of his American peers made this explicitly.

Instead of making the same point over and over, the album creates a context of blackness with frequent references to Jamaican culture, while keeping in mind that “Africa is the foundation.” Rather than hogging the spotlight, Rebel MC is the host of a soundsystem, often stepping back in favor of the music or other vocalists. He invites an elder Dennis Brown to revisit one of his earliest tunes on “No Man Is an Island,” Barrington Levy, Super Cat and Tenor Fly can be heard on “Tribal Base,” and a number of international reggae and R&B artists make contributions.

Musically, some numbers can be categorized as contemporary UK soul in the vein of Soul II Soul – the aforementioned “No Man Is an Island,” the wide-scope “Soul Rebel” (“With a drummer drummin’ beats from the old school”) or “Word of the Ghetto,” where Rebel strengthens his belief in the mission he’s embarked on:

“It’s the word of the ghetto, run out the slack rap

As I pull a crisp wax from the lyrical hat

Not the mad, mad hat or the hat of the wack

But the hat of the teacher; mind the mouse trap

set by society, to excercise the fact

that you’re gonna get stress if your colour is black

‘No,’ some say, ‘that’s not the way

Chat like that, your tracks won’t get played

Stick to the formula ya had before

Fame and money and a whole lot more’

Cha! Wheel out ah dat, seh dat can’t be

I gotta true-speak intelligently

Maybe for that I might sacrifice sales

but I’ll put more weight on the justice scales”

After these back-to-back smooth tunes, “Black Meaning Good” switches to a more dance sound. Reflecting the burgeoning UK electronic scene of the late ’80s and early ’90s, uptempo breakbeats back up tracks such as “Comin’ on Strong” and “Soul Sister” while “Afrikan” and “Culture” mix dub sounds and roots reggae, respectively, with more modern electronic elements. What’s more, with “The Wickedest Sound” and “Tribal Base” Rebel MC became nothing less than one of the godfathers of jungle, the layered breakneck drums, vocal loops, bleeps and stabs making them forerunners of jungle and drum ‘n bass. In fact, after one more album as Rebel MC, the Londoner faded into the underground, becoming a full-fledged junglist working under a multitude of monikers, running various labels, releasing influential tunes and even reuniting with DJ Ron, his musical partner from the ’80s in the group Micron, responsible for the previously mentioned “EastEnders” rap.

You couldn’t really see it coming in 1991, but “Black Meaning Good,” while at first glance looking like a predictable attempt to gain credibility, was a vision of things to come. Sampling sites list several classic hip-hop breaks being used across the album. But their use is far from obvious, including The Winstons’ “Amen, Brother,” who accidentally would become the construction kit for countless drum ‘n bass tracks. And as you listen to Rebel rap about beatmaking in the closing “Test the Champion,” you realize that his career reflects the UK’s recurring musical journey from imitation to innovation.