“See, the moral of the story is

I’m not here to replace Notorious

I’m just a young cat tryin’ to do his thing

Harlem World style, pursue my dream”

(“Do You Wanna Get $?”)

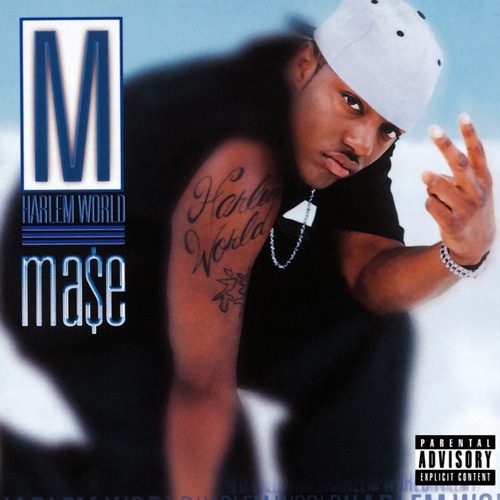

In interviews Mason Betha would explain the title of his debut by offering that being on the road with Puffy enabled him to see the world, but that upon returning to his stomping grounds, he realized that there was no place like home. To the young rap star “Harlem World” therefore stood for where he came from and where his career had taken him. But as a name, Harlem World had been in use long before Mase’s 1997 debut album and the following crew project “The Movement” under the Harlem World handle. Harlem World was the name of a club located on 116th Street and Lenox Avenue, where famous battles between the Cold Crush and the Fantastic 5 and between Busy Bee and Kool Moe Dee took place. Dr. Jeckyl & Mr. Hyde used to go by the name Harlem World Crew when they recorded “Rappers Convention” and “Love Rap.” Mase, obviously aware of the origin of the phrase but too young to be a regular at the club, set out to resurrect the glory days of hip-hop in Harlem. In hip-hop geography, Harlem comes just after the Bronx, as the place that offered professional venues for the park DJ’s of the Bronx, where said DJ’s took clues from jocks like Pete DJ Jones, Eddie Cheba, June Bug, Love Bug Starski and DJ Hollywood, and last but not least as the home of early rap stars such as Kurtis Blow, the Treacherous Three, the Crash Crew and the Fearless 4.

Many years later five Harlemites would form a rap crew known as Children of the Corn. They were Killa Kam, Bloodshed, Big L, Herb McGruff and Mase Murda. Two of them died an untimely death, two lived to become international rap stars. Big L attained that position post mortem in 1999, Cam’ron’s cousin Bloodshed died in a car accident. Out of the five, Mase found stardom the soonest when he joined the Bad Boy camp in 1996 after travelling to an industry conference in Atlanta with the intention to impress Jermaine Dupri. That same year, Mase, having defused his murderous moniker, was the remix rapper on 112’s “Only You” and assissted Puff Daddy on his first single “Can’t Nobody Hold Me Down.”

By the time he made his full-length debut, Mase was hated as much as he was loved. He was Puffy’s main accomplice in making sure that after Big’s death the Bad Boy express didn’t come to a halt. Together they were the embodiment of what became known as the shiny suit era. By making rap get comfortable with R&B (and vice versa), Bad Boy came to stand for the definite incorporation of rap music into pop music. And M-a-dollar sign-e was everywhere, the latest hip-hop heart-throb appearing in video clips to BIG’s “Mo Money Mo Problems,” Puff’s “Been Around the World” and his own “Feel So Good.”

Maybe it’s a reflex hip-hop fans acquire since “I Need Love,” but a lot of us know that the singles can present a totally different rapper than the album minus those singles. A bad single can even be an indicator of a better album, because often labels will pick the least daring song for a single. It was no different with “Feel So Good.” Sean ‘Puffy’ Combs and Deric ‘D-Dot’ Angelettie were satisfied with sampling Kool & The Gang’s “Hollywood Swinging” and letting singer Kelly Price quote bits from Miami Sound Machine’s “Bad Boys.” It was an instant hit, as Mase, mumbling his way through the unremarkable track, dictated a new rap language: “It’s like y’all be talkin’ funny / I don’t understand language of people with short money.”

Lacking any artistic ambition, the Mase of “Feel So Good” couldn’t have replaced Notorious even if he wanted to. There was another side to Mase, though, and while the combination of both was rather problematic, I for one was glad “Harlem World” didn’t merely consist of variations of “Feel So Good.” My low expectations being surpassed was probably the main reason I played this album rather excessively. Although I was highly sceptic, Mase managed to win me over with the obvious effort he put into his lyrics and a handful of thoroughly nice songs.

I didn’t mind how he bit LL Cool J for “Lookin’ At Me,” because it was evident that Mase came from the same position as LL who asked harrassing cops in 1989, “Can’t a young man make money any more?” Eight years later Mase repeated that line from “Illegal Search,” and in my opinion he had every right to. The problem lay elsewhere. Mase was Puffy’s puppet. He said it himself: “I was Murda, P Diddy named me Pretty / Did it for the money, now can you get with me?” Despite his claim to not be a substitute, it looked like Mase was to be a more accessible Biggie, since the latter’s junior partner Lil’ Cease didn’t quite have the potential (and on top of that stayed loyal to Lance ‘Un’ Rivera). After all, didn’t he introduce himself as the “newest member of the Bad Boy team” who was going to “bring this nigga Puff mad more cream / with hooks galore,” hoping to “take ’em back where Biggie took ’em before”?

Promoting “Harlem World,” a surprisingly honest Mase told Beat Down magazine: “I have to do what it takes to make the money and come out paid. Yeah, I got caught up in the materialistic rhymes and that’s not hip-hop. I don’t like “Can’t Nobody Hold Me Down” at all, but it sold three million records. So, it’s not what I like, it’s what the people want to hear.” He basically made the same argument on his album, down to “The thing that went three mill I didn’t even like.” Ultimately it’s up to the artists to determine to what degree they want to compromise. They just have to be aware that if they do, people might find out about it and think they’re taking it too far. In this particular case most people would probably agree that writing AND performing material that you don’t really like comes close to self-denial. And yet the music industry is full of one-hit wonders who make a living playing songs they’ve long grown tired of. We expect artists to work for next to nothing while breaking the mold with every new creation, but how many of us hate their dull jobs? For Mase it was simple: “You cats keepin’ it real, you cats is on your own / cause bein’ broke and alone is somethin’ I can’t condone.”

What you witnessed on “Harlem World” was hustling theory being put into practice. You know, that whole ‘If it don’t make dollars it don’t make sense’ thing. In Mase’s own, disarmingly frank words: “I was Murda for six years, seen no cream from it / dropped Murda off Mase, woke up at Teen Summit.” In the aforementioned interview he continued, “I’ll be honest with you, I hate my rap on “Only You,” but Puff said, ‘Just ride with it.’ Puff and I get into lots of arguments about production and other things. But basically it boils down to this: ‘Do you want to get paid?’ It’s not really what I’m going to do but what we [Puffy and I] are going to do. I like to do the music that will please the homies on the block, but Puff tells me, ‘That’s only going to get you handshake and you can’t pay the bills with that.’ The people on the block will say, ‘Yo Mase, that was ill and you’re keeping it real with the hip-hop,’ and that’s what I want to happen, you know what I’m sayin’? But in reality, I won’t have a dime to show for it and I’ll go broke with that.”

Obviously generating cash flow will only get you so far as an artist. Longevity comes also from idealistic impulses, artistic aspirations and the longing for independence. Just ask Dr. Dre. Ask Scarface. Ask Jay-Z. Ask KRS-One. Ask Too $hort. Ask Snoop Dogg. At some point they all had to withstand the temptation of following the latest trend. The problem with “Harlem World” (and many other rap records) is that it is hard to determine how much the artist really goes against the grain. Considering Puff’s heavy involvement, it’s a safe bet that the more ‘street’ offerings were part of the package. Conceptually that would have been nothing new. Starting with LL Cool J, the most sucessful rappers have always catered to the teens and the clubbers as well as to the hardrocks and the connoisseurs. Singles usually spell mass appeal, album cuts often beg for street cred or lyrical props.

In Mase’s case, it was most likely the rapper’s own input plus Bad Boy’s business sense that lead to a considerable amount of violence on what most people expected to be a pop rap album. To let the man himself sum it up: “Shock niggas / who thought I was a pop nigga / You go against Mase, you get your wig rocked, nigga.” After “Feel So Good,” such words definitely came as a shock. Considering the fact that young girls made up a good part of Mase’s target audience, the strangest offering was “I Need to Be” featuring singer Monifah. Not only was it clearly pornographic, touching the topic of sex with minors gave it a disturbing twist you’d expect from a Biggie record.

In terms of gunplay, it was evident that that had been a big part of Mase’s background as an underground rapper. A pre-debut DMX assists him on the hook of “Take What’s Yours,” while Mase has us looking down the barrel of his gun:

“I let one loose to show you I ain’t the one, duke

And I ain’t bluffin’ nothin’, nigga, all my guns shoot

You let your dun loose, none ’em niggas gun-proof

Watch them niggas drop when I pop one in they sunroof

And we be lead-bustin’, leavin’ niggas’ head gushin’…”

Ironically, considering the material Mase blew up with, you would have thought that it was not the shiny suit but the guntalk that was being forced upon the young rapper. Either way, the criminal energy is used creatively on the posse cut “24 Hrs. to Live,” which also features DMX, Black Rob and The LOX. The concept is well executed by all six rappers. Even Puff’s hook somehow fits in. I’d wager that New York’s hottest underground MC’s of the time couldn’t have done better. The similar “Will They Die 4 You?” doesn’t quite measure up. Maybe it’s because the song asks such a melodramatic question while Lil’ Kim manages to be more menacing than Mase and Puff combined, maybe it’s because the beat uses a sample that is either associated with EPMD’s “Get the Bozack” or the immensely popular DMX single that was just around the corner, “Get at Me Dog.”

Of the darker tracks, none was as intriguing as “Wanna Hurt Mase?” Its epic yet light beat is the equivalent of a chilling breeze. Something compelled the producers to note that the track ’embodies portions of’ Culture Club’s “Do You Really Want to Hurt Me,” but the credit is really all due to Puffy and Ron ‘Amen-Ra’ Lawrence for their layered track that embodies the next level shit Bad Boy was also capable of. Mase complied, sounding surprisingly cold on this one:

“Now you don’t wanna see me angry

Ain’t enough cops or cuffs to chain me

Days to arraign me, KKK’s to hang me

Insanely, you need ice picks to bang me

Need more than a straitjacket to restrain me

Or more guns with my prints for you to frame me”

All things considered, what ultimately won me over was the fact that although polished, “Harlem World” wasn’t glossed over with a typical pop sound. There was a certain cool to it that Puff had been perfecting since he left Uptown to start Bad Boy. For the opening “Do You Wanna Get $?” D-Dot and Amen-Ra come up with a distinctly jiggy beat, but the uncredited singer (Faith Evans?) adds an absolutely intriguing touch with her icy whisper: “With all this money that we can we can make / why y’all cats wanna player-hate?” The album’s second single, “What You Want,” was equally subliminal thanks to a grounded guitar loop and the Total feature. Mase kept it strictly for the ladies with enough humor and depth to make this a sophisticated pop rap single:

“Now Mase be the man wanna see you doin’ good

I don’t wanna get rich, leave you in the hood

Girl, in my eyes you the baddest

The reason why I love you, you don’t like me cause my status

I don’t wanna see you with a carriage livin’ average

I wanna do my thing, so we be established

And I don’t want you rockin’ ’em fabrics

Girl, I wanna give you carats till you feel you a rabbit

Anything in your path want you can have

Walk through the mall, if you like it you can grab

total it all up and put it on my tab

and then tell your friends all the fun you had”

A bad example of a radio-friendly joint would be “Love U So,” which also jacked two songs at the same time, this time “Square Biz” for the beat and “Ooh Boy” for the hook. As the mumble becomes even more unintelligible, you begin to wonder if Mase is simply embarrassed by his “In the club jingle like I’m Jell-o big as Tickle-Me-Elmo” lyrics and the fact that he “would’ve did more without censorship.” “Cheat on You” features a then-typically sober Jay-Z along with Lil’ Cease over a Jermaine Dupri beat. Seeing how “In My Lifetime Vol. 1” dropped around the same time, it’s safe to say that at this particular moment in time Mase was the bigger star than Jay. The Neptunes weren’t nearly as big as they would soon be either, but the creeping “Lookin’ at Me” hints at their club potential.

A duo with particular notoriety guested on “The Player Way.” Two years before Jay featured UGK on “Big Pimpin’,” “The Player Way” was the first major southern feature on a New York release since 1992’s “Two to the Head.” Eightball & MJG bring along T-Mix to produce the classiest beat of the album and present their refined flows, to the point where Mase essentially guests on a Suave House track. “Bad Boy, Suave House, one of the many connections we gon’ make as black entrepreneurs,” promised Puffy towards the end, but not even he could have guessed that the Memphis veterans would one day be Bad Boy’s most experienced act.

As a black entrepreneur, Puff Daddy expertedly engineered “Harlem World” into a success. With four million copies sold it was one of the decade’s many multi-platinum albums. It was a well done, sometimes even ambitious album. The way Dame Grease and Richard ‘Younglord’ Frierson used Busta Rhymes on “Niggaz Wanna Act” let you know that these people knew what they were doing. In his interview with Beat Down Mase announced that the album would feature contributions from DJ Premier and Easy Mo Bee. He also hoped to rap over beats by The RZA and Trackmasters. In the end, none of these people appeared on it. In all likeliness it wasn’t Mase who decided against them. If you want to get cynical about it, what Puff says above is that “The Player Way” was a business venture before it was a collaboration of artists. Maybe that was true for all of the tracks, and Mase was simply the MC to make selling out fashionable.

Just like it serves as an indication as to why indie rap would come back strong during those years, “Harlem World” is a testament to Bad Boy’s can-do-no-wrong confidence of the mid-’90s. The guy has a mumble? Don’t worry, we will make them love it! As long as he isn’t humble… To Mase’s credit, many times he came off kind of cool, an impression fueled by his nasal, nonchalant tone and relaxed delivery. As a rapper, he wasn’t fresh at all, but he somehow managed to be fly, expressed on a lyrical level in a mixture of cockiness and politeness, slightly reminiscent of Slick Rick. Say what you want, it’s hard to pick apart an argument like “Went from hard to sweet / starve to eat / from no hoes at shows to ménages in suites / Now I be the cat that be hard to meet / gettin’ head from girls that used to hardly speak.” At the same time there’s just too much of that, to the point that even he acknowledges, “I’m dyin’ from a sickness known as willie-ism.” In which case his last breath would’ve been the closing “Jealous Guy,” a poor imitation of BIG’s “Playa Hata.” What was that about Notorious again?